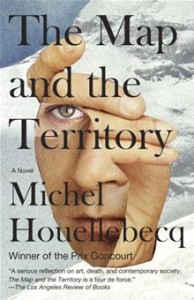

Yesterday I finished reading Michel Houellebecq’s Prix Goncourt-winning novel The Map and the Territory. (Not to be confused with Alan Greenspan’s treatise of the same name.) A rather short book (the paperback version clocks in at 269 pages), it was originally written in French (La carte et le territoire) and translated into English by Gavin Bowd.

Yesterday I finished reading Michel Houellebecq’s Prix Goncourt-winning novel The Map and the Territory. (Not to be confused with Alan Greenspan’s treatise of the same name.) A rather short book (the paperback version clocks in at 269 pages), it was originally written in French (La carte et le territoire) and translated into English by Gavin Bowd.

It was, in general, an easy read. I wouldn’t place it among my favorites, but then meditations on human deterioration and eventual death — the preoccupations of the Louis CK set, so to speak — were never my forte to begin with.

What caught my attention more, however, was the translation itself. One of the striking features of the novel is the author’s insertion of himself — or some twisted literary version of himself — into the story. Because Houellebecq plays such a central role in the narrative, the book begins to get creative with its references to him. In addition to simply referring to him as Michel Houellebecq, he is alternatively described thusly:

- “He rang the doorbell and waited for about thirty seconds, and the author of The Elementary Particles came to open the door, wearing slippers, corduroy trousers, and a comfortable fleece of undyed wool.”

- “‘That’s a magnificent subject, fucking fascinating even, a genuine human drama!’ the author of Platform enthused.”

- “He hammered on the door for at least two minutes, under a heavy downpour, before Houellebecq came to open it. The author of The Possibility of an Island was wearing gray-striped pajamas that made him vaguely resemble a prisoner in a television series; his hair was ruffled and dirty, his face red, almost with broken veins, and he stank a little.”

- “Nevertheless, the poet of The Art of Struggle stepped back a meter, just enough to allow Jed to take shelter from the rain, without, however, really giving him access inside.”

- “‘Just one bottle?’ asked the poet of The Pursuit of Happiness while stretching his neck toward the label.”

After noticing many of these constructs throughout the book, I began to think this was some sort of literary in-joke: Michel Houellebecq using a fictional version of himself to promote his oeuvre. But several elements conspired against this interpretation as I continued reading. First, Houellebecq wasn’t the only author referred to by the titles of his books, thereby eliminating shameless self-promotion as the likeliest explanation.

Secondly, other parts of the book were clunky as well. In the second excerpt above, for example, “enthused” is used to describe Houellebecq’s statement. As the late novelist Elmore Leonard once wrote, “Never use a verb other than ‘said’ to carry dialogue. The line of dialogue belongs to the character; the verb is the writer sticking his nose in.”

Finally, there were a few tell-tale passages that betrayed the original French lurking just beneath the English translation (even though Gavin Bowd, the translator, is a native Scotsman). One is the following:

Even if he speaks at length about it over several pages, the camera equipment used by Jed had, in itself, nothing very remarkable about it: a Manfrotto tripod, a Panasonic semi-professional cameoscope — which he’d bought for the exceptional luminosity of its sensor, allowing him to film in almost total darkness — and a hard disk of two teraoctets linked to the USB outlet of the cameoscope.

(Emphasis mine.)

“Teraoctet” is, of course, the French translation of “terabyte.” Similarly:

It was the last important decision he had to take in his life, and Jed feared that this time again, as he used to do when encountering a problem on his building site, he would choose to make a clear-cut choice.

(Emphasis mine.)

“Taking” a decision, as opposed to making one, is another quintessential French-ism (from prendre une décision).

Evaluated separately, none of these linguistic tics is particularly noticeable. But the cumulative effect is to cast doubt on the effectiveness of the translation as a whole: The Map and the Territory, obsessed as it is with the distinction between a representation and that which is represented, requires a certain delicacy of language.

Bowd appears to have drawn the line at a literal translation: where the French version referred to Michel Houellebecq as the author of The Elementary Particles, for instance, Bowd apparently did the same in English, every time. But it is entirely unclear to my (decidedly non-fluent in French) eyes whether the true meaning was just as accurately conveyed in English as it was in the original French. Here, too, the map is certainly not the territory.

Related articles

Post Revisions:

- February 1, 2014 @ 18:21:45 [Current Revision] by Jay Pinho

- February 1, 2014 @ 18:21:45 by Jay Pinho

I have just found this comment on the translation of Houellebecq’s La carte et le territoire. I myself read it in French some years ago and greatly admired. I recently acquired the English translation and have been so disturbed by it that I googled the translator and found this. Well, now I know it’s not just me and I can assure Jay Pinho that his own reservations are fully justified. I had no idea who the translator was until I googled him and had seriously begun to wonder whether English was his first language. It’s all very strange.

Simon Wilson

Hello, currently re-reading The Possibility of an Island in Gavin Bowd’s translation and am struck again (many years later) by the unusually awkward phrasing, poor word choice etc. I’ve read other Houellebecq works in French and this translation is just, well, flawed to say the very least. Glad to know i’m not alone in this, thanks for posting.