Continuum – Young & Sick

Continuum – Young & Sick

Noah Newkirk of Los Angeles made national headlines yesterday when he interrupted an oral argument in the Supreme Court with a protest over the Court’s 2010 decision in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission. Newkirk, who had been admitted into the courtroom as a spectator, stood up and made his statement toward the end of arguments for Octane Health LLC v. Icon Health and Fitness, Inc.–a case that involved patent attorneys’ fees, not campaign finance–before being promptly removed by security. Because cameras are not permitted in the courtroom and the Supreme Court does not broadcast its oral arguments live, initial media accounts of the disruption either summarized or quoted only snippets of what Newkirk reportedly said, while the court’s official transcript of the Octane oral argument left out the protest entirely.

Thanks to new video released by a YouTube user named “SCOTUSpwned,” however, we can now see footage of Newkirk’s protest in full, which was clandestinely recorded (and captioned) by an anonymous person sitting in the spectators’ section with Newkirk yesterday. In addition, SCOTUSpwned also posted five other secretly-made videos from two different Supreme Court oral arguments from this term, ranging from four seconds to half an hour in length. I’ve watched all of them and identified the relevant oral arguments where I can, which I describe below. We begin with the first video that SCOTUSpwned uploaded:

Video 1 (MOVI0000) – Timestamped 10/08/13

Burt v. Titlow (argued 10/08/2013): 16 minutes into the video, you hear one of the attorneys, John J. Bursch, say, “[Y]ou can see how that difference played out in this very case because the Sixth Circuit didn’t look at all the other evidence …,” which matches page 55 of the transcript of the Titlow oral argument.

Video 2 (SUNP0000) – Timestamped 1/25/08

It is inconclusive where this was taken, since the video only lasts 4 seconds. Based on the timestamp, however, I believe this was recorded during the same session, by the same person, as Video 4 (which was of the Burt v. Titlow oral argument; see below).

Video 3 (MOVI0036) – Timestamped 1/1/2008

Octane Fitness v. Icon Health & Fitness (argued 2/26/2014): 34 seconds into the video, you can hear attorney Carter G. Phillips say, “And then when Congress, in 1952, incorporates the exceptional case standard…” which matches the argument on p. 32 of the transcript.

Video 4 (SUNP0001) – Timestamped 1/25/2008

Burt v. Titlow (argued 10/08/2013): Around 38 seconds into the video, Valerie Newman says, “It appears from the record that he got his information from the media. This was a highly, highly publicized case,” which corresponds with p. 50 of the transcript.

Video 5 (SUNP0019) – Timestamped 6/14/2008

Octane Fitness v. Icon Health and Fitness (argued 2/26/2014): 50 seconds in, Roman Martinez says, “Here Congress did not say otherwise. Congress did not embrace a clear and convincing standard,” which matches the dialogue on p. 26-27 of the transcript.

Video 6 (“Supreme Court caught on Video!”) – Timestamped 10/08/13 [UPDATED]

Burt v. Titlow (argued 10/08/2013), Octane Fitness v. Icon Health and Fitness (argued 2/26/2014): This video contains footage from two separate oral arguments. The first 1:10 is from Titlow–although it is mislabeled in the video as “the oral arguments… for the case McCutcheon v. FEC” (which was argued the same day as Titlow, but is not the same case). At the 50-second mark, we can hear Valerie Newman, Titlow’s attorney, say “She had already pled, so she had already entered a plea, and all that was left was sentencing,” which matches p. 50 of the argument transcript. The last half of the video is from yesterday’s Octane Fitness v. Icon Health argument and includes Noah Newkirk (captioned as “Kai” in the video) asking the justices to overrule Citizens United. Newkirk waits until Carter G. Phillips says, “If there are no other questions, your honors, I’d urge you to affirm” (p. 48 of the Octane argument transcript) before standing up and protesting. The video then shows him being removed from the courtroom. The anti-corruption grassroots group 99rise, of which Newkirk is a co-founder, took responsibility for the protest and issued a press release that included the full speech Newkirk made in court.

[UPDATE: The original version of this post misidentified the first minute and ten seconds of the video as coming from the McCutcheon v. FEC oral argument, in part due to the caption of the videographer and in part due to the fuzziness of the audio–I believed the female voice I heard was Erin Murphy, a lawyer for the McCutcheon appellants. Upon further audio analysis, however, I realized that the words the female attorney was saying matched up not with the McCutcheon argument transcript but the Burt v. Titlow transcript, and that the voice was Valerie Newman’s rather than Murphy’s. None of the six videos on SCOTUSpwned’s YouTube page are from McCutcheon v. FEC. I regret the error.]

As far as I can tell, these are the first videos of the Court in session to go public, sparking online discussion about the identity of the cameraman, the method they used in compiling this footage (what did they use to film the Court, and how did they get it past security?), and whether this incident might ultimately push the Supreme Court toward or away from allowing live broadcasts of its proceedings.

I’m also wondering whether we can expect a “sequel” from 99rise anytime soon. It appears from the differing timestamps and varying audio quality on some of the videos that multiple people managed to sneak devices in and film the Court (Video 1, for instance, bears the correct date for the oral argument in Burt v. Titlow but makes it difficult to hear the words of the attorneys because it captures mostly the breathing of the cameraman, whereas Video 4 of the same oral argument has an incorrect timestamp but much cleaner audio), but to date, only Noah Newkirk has been thrown out for causing a disturbance. It is unclear whether any other collaborators were caught recording the arguments during yesterday’s scuffles. Since the group obviously cares a great deal about the Court’s campaign finance jurisprudence and made a point to be physically present on the day of the McCutcheon argument (Burt v. Titlow, after all, was argued on the same day as McCutcheon), I’m guessing that they were at the Court yesterday because they believed that the justices were going to issue a ruling in McCutcheon. That didn’t turn out to be the case, but what will they have planned when the Court actually does, and how does Court staff plan to tighten security before that day comes?

Well, this went about as well as could be expected:

By its very nature, House of Cards invites discussion. It entire first season was foisted upon us all at once last February as an early Valentine’s Day present: a tale of escalating palace intrigue that culminated, in Episode 11, with the shocking (and somewhat absurd) murder of Congressman Peter Russo. Season 2, which was released — en masse, once again — to much fanfare on Friday, provoked even larger ripples online, eliciting the ritual thinkpieces, interviews, and meta-analyses.

You’ll forgive me, then, for wading in myself. As a binge-watcher of Season 2 (I finished the finale sometime after midnight on Monday), I fell prey, like so many others, to the seductive guile of Frank Underwood as he marched his way straight into the Oval Office.

Let’s leave plot contrivances aside for a moment. House of Cards may fancy itself pop culture’s sharpest purveyor of political realism, but its broad narrative brushstrokes are nothing if not impressionistic. (Either that or I’m not nearly paranoid enough about my elected officials.)

Much of the conversation sandwiching the release of the second season centered on House of Cards‘ innate cynicism. Ian Crouch, writing for The New Yorker, for example, explained the show’s ethos thusly:

“House of Cards,” back now with its entire second season streaming on Netflix, is a show about contempt. There is contempt in the general, interpersonal sense: the politicians, operatives, journalists, and various other D.C. types all hold one another in especially expressive disregard. (Last season, Francis Underwood, played by Kevin Spacey, explained his relationship to his colleagues like this: “They talk while I sit quietly and imagine their lightly salted faces frying in a skillet.”) And there is contempt in the legal sense—the plots turn on the subversion and manipulation of rules and regulations, and the breaking of laws (murder, etc.) for personal gain and professional advancement. Ethics, like feelings, are obstacles, and beneath consideration.

Crouch goes on to claim, rather convincingly, that the series saves its most ferocious contempt for its own audience: “We are the ones, after all, who tolerate and thus perpetuate the real-life theatre of venality and aggression from which ‘House of Cards’ derives its plausibility.”

As a description of the political status quo, this is certainly true. Crouch, however, clouds his thesis by emphasizing the cockiness of Beau Willimon, the showrunner whose elimination of yet another principal character in the Season 2 premiere showcased, Crouch reports, “a power trip in which the show and its main character assume parallel roles as bullies.”

While this is a perfectly defensible interpretation of the relationship between House of Cards and its enraptured fan base, it is not, I think, the most accurate one. Contempt implies strength of feeling: it is, after all, one of the telltale signs of a marriage in dissolution. Admittedly, it is often a sign of power inequality as well: the strong feel contemptuous of the weak, not vice versa. Nevertheless, contempt connotes a vigorous degree of hostility.

But it is this precise feature — red-faced rage and its emotionally-charged cousins — that is almost entirely absent from House of Cards‘ dalliance with its viewership. On this, Todd VanDerWerff of A.V. Club hits the right note:

Midway through the season-two finale of House Of Cards, Kevin Spacey’s Francis Underwood confronts one of the many people incredibly pissed off at him backstage at the opera. (It has to be the opera, for House Of Cards does not do subtlety.) The conversation is interrupted by a patron who exits the auditorium, presumably looking for a bathroom. They look over at her as she walks through—both seemingly miffed that she even exists. It’s a scene that summarizes House Of Cards’ relationship to the average American citizen: Everybody in this country is grist for the mill for politicians like Frank, who serve only themselves and carry out their real deal-making far behind the scenes of what’s available to the press and C-SPAN. And don’t you think you have the right to know about it. At best, you’re an irritating inconvenience. At worst, you’re dead.

Contempt is for threats; rivals, even. Contempt is what drove Frank Underwood to send Peter Russo to his makeshift gas chamber in Season 1 and Zoe Barnes to her early demise in Season 2. It is, as a general rule, the principal sentiment vaulting Underwood’s entire career past those of his peers in the House of Representatives and beyond.

But a clear line separates the contempt pervading nearly all of House of Cards‘ interpersonal relationships from its most crucial one by far: that of Frank Underwood’s with the audience. When, in the new season’s premiere, Kevin Spacey at last addresses the viewer, he gazes not directly into the camera, as is his wont, but through a bathroom mirror. As he speaks, the camera pulls in slowly until the frame edging the glass is almost completely obscured: Frank Underwood has met his reflection, and it is us.

Did you think I’d forgotten you? Perhaps you hoped I had. Don’t waste a breath mourning Miss Barnes. Every kitten grows up to be a cat. They seem so harmless at first—small, quiet, lapping up their saucer of milk. But once their claws get long enough, they draw blood. Sometimes from the hand that feeds them. For those of us climbing to the top of the food chain, there can be no mercy. There is but one rule: hunt or be hunted. Welcome back.

Ian Crouch views this parting scene as evidence of Willimon’s arrogance:

And then there is one last shot, in case there was any confusion as to the message: a pair of silver cufflinks bearing Frank’s initials. They’d been mentioned before—a birthday gift from his body man—and, called back, they make for a funny visual gag: “F.U.” … We’ve been told, as the Times likes to say, to “commit a physically impossible act.” Frank despises most everybody—why should we be an exception?

But here Crouch misunderstands Underwood and, by extension, Willimon. “F.U.” is the precise opposite of a “power trip:” it is, rather, the ultimate invitation to an insiders’ club. It is a joke so obvious it begs to be understood, a wink that demands a knowing nod. As a sophomoric sight gag, “F.U.” is a souvenir to its audience. But as an epithet, “F.U.” is decidedly not a message to those of us who watch House of Cards: it’s a contemptuous insult for everyone who doesn’t.

From this perspective, the message of House of Cards is remarkably consistent. It is no accident that an unsubtle version of Politico — an online-only publication dubbed Slugline — serves as the most formidable opponent of Underwood as he rapidly scales the Washington political ladder. Indeed, it is only the murder of its most intrepid reporter that reestablishes Underwood’s control over his own destiny, an objective that could only be derailed by a consummate insider such as Zoe Barnes. In a two-season narrative arc dedicated to highlighting Frank Underwood’s utter mastery of his domain, the single common thread uniting him to all of his peers in House of Cards is their overwhelming collective insulation from life outside the Mall.

Indeed, the fiercest contempt in the series is reserved for all of The Others: those who believe in a democratic politics, the power of representative elections, education reform, foreign policy initiatives, the national interest. People who didn’t catch “F.U.” Simpletons, one and all.

Is anyone really supposed to care about any of the particular policy battles waged throughout the first two seasons? Do we even remember what they were? Of course not: we’re here for the spectacle. We’re here, in short, to become insiders too. It is in this arena that House of Cards excels: it masterfully inhabits the universe populated by our politicians and the hordes of journalists who mob their every prepackaged press conference and giggle over their every wayward tweet. Contempt for the real world goes without saying. We are all complicit in trading away accountability journalism for tabloid-style coverage of the daily political grind, and House of Cards is our soma.

Todd VanDerWerff neatly captures this addiction to irrelevance towards the end of his review:

Yet House Of Cards is also weirdly perfect when it comes to what it’s meant to do, which is keep viewers plowing through episodes, regardless of time spent doing so. There are just enough flourishes around the edges…that it’s possible to feel like House Of Cards has something deeper on its mind, even when it’s all but clear it doesn’t. This is sleight of hand that works much better in the middle of the binge, rather than a few hours later, when contemplating whether the plot made any sense.

VanDerWerff appears, at first glance, to be damning House of Cards with faint praise. But it is really quite the opposite: in portraying Washington as a city full of sound and fury, signifying nothing, House of Cards has in fact perfectly captured the reality of modern politics in the era of horse-race journalism.

Proof that supply and demand are not always in perfect equilibrium, at least in the realm of quality journalism:

What a contrast. Silicon Valley: where ideas come to launch. Washington, D.C., where ideas go to die. Silicon Valley: where there are no limits on your imagination and failure in the service of experimentation is a virtue. Washington: where the “imagination” to try something new is now a treatable mental illness covered by Obamacare and failure in the service of experimentation is a crime. Silicon Valley: smart as we can be. Washington: dumb as we wanna be.

Tom Friedman is the most embarrassing of a truly amateur-hour op-ed operation at the Times.

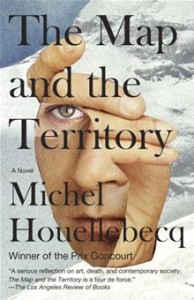

Yesterday I finished reading Michel Houellebecq’s Prix Goncourt-winning novel The Map and the Territory. (Not to be confused with Alan Greenspan’s treatise of the same name.) A rather short book (the paperback version clocks in at 269 pages), it was originally written in French (La carte et le territoire) and translated into English by Gavin Bowd.

Yesterday I finished reading Michel Houellebecq’s Prix Goncourt-winning novel The Map and the Territory. (Not to be confused with Alan Greenspan’s treatise of the same name.) A rather short book (the paperback version clocks in at 269 pages), it was originally written in French (La carte et le territoire) and translated into English by Gavin Bowd.

It was, in general, an easy read. I wouldn’t place it among my favorites, but then meditations on human deterioration and eventual death — the preoccupations of the Louis CK set, so to speak — were never my forte to begin with.

What caught my attention more, however, was the translation itself. One of the striking features of the novel is the author’s insertion of himself — or some twisted literary version of himself — into the story. Because Houellebecq plays such a central role in the narrative, the book begins to get creative with its references to him. In addition to simply referring to him as Michel Houellebecq, he is alternatively described thusly:

After noticing many of these constructs throughout the book, I began to think this was some sort of literary in-joke: Michel Houellebecq using a fictional version of himself to promote his oeuvre. But several elements conspired against this interpretation as I continued reading. First, Houellebecq wasn’t the only author referred to by the titles of his books, thereby eliminating shameless self-promotion as the likeliest explanation.

Secondly, other parts of the book were clunky as well. In the second excerpt above, for example, “enthused” is used to describe Houellebecq’s statement. As the late novelist Elmore Leonard once wrote, “Never use a verb other than ‘said’ to carry dialogue. The line of dialogue belongs to the character; the verb is the writer sticking his nose in.”

Finally, there were a few tell-tale passages that betrayed the original French lurking just beneath the English translation (even though Gavin Bowd, the translator, is a native Scotsman). One is the following:

Even if he speaks at length about it over several pages, the camera equipment used by Jed had, in itself, nothing very remarkable about it: a Manfrotto tripod, a Panasonic semi-professional cameoscope — which he’d bought for the exceptional luminosity of its sensor, allowing him to film in almost total darkness — and a hard disk of two teraoctets linked to the USB outlet of the cameoscope.

(Emphasis mine.)

“Teraoctet” is, of course, the French translation of “terabyte.” Similarly:

It was the last important decision he had to take in his life, and Jed feared that this time again, as he used to do when encountering a problem on his building site, he would choose to make a clear-cut choice.

(Emphasis mine.)

“Taking” a decision, as opposed to making one, is another quintessential French-ism (from prendre une décision).

Evaluated separately, none of these linguistic tics is particularly noticeable. But the cumulative effect is to cast doubt on the effectiveness of the translation as a whole: The Map and the Territory, obsessed as it is with the distinction between a representation and that which is represented, requires a certain delicacy of language.

Bowd appears to have drawn the line at a literal translation: where the French version referred to Michel Houellebecq as the author of The Elementary Particles, for instance, Bowd apparently did the same in English, every time. But it is entirely unclear to my (decidedly non-fluent in French) eyes whether the true meaning was just as accurately conveyed in English as it was in the original French. Here, too, the map is certainly not the territory.

In tomorrow’s New York Times Magazine, Amy Chozick delves into the political intrigue surrounding Hillary Clinton’s presidential ambitions. The online hubbub over the article, titled “Planet Hillary,” actually began on Thursday, when the magazine cover art was released, to widespread bewilderment:

Hillary Rodham Clinton, as you've never seen her, on the cover of this Sunday's NYT Magazine pic.twitter.com/QIsqibZaq5

— David S. Joachim (@davidjoachim) January 23, 2014

Anyway, I got around to reading the piece today and couldn’t escape an uneasy feeling about it. It took me a few minutes to realize that “Planet Hillary” was a vintage Politico-esque creation. It deals almost entirely in political maneuvering and the “who’s-in-who’s-out” hysteria endemic to public figures and their extensive entourages. More damningly, it is almost completely devoid of policy discussion.

Granted, there is a place in political journalism for fluffy, narrative-driven, gossip-heavy recaps of the Washington social ladder. But generally speaking, The New York Times has not been that place. (The reliability of that axiom is one major reason I’m a subscriber.) In fact, it is perhaps because of the Times’ historical reticence to portray the constant power shuffling within American politics as equivalent to its counterpart in a typical high-school cafeteria that “Planet Hillary” seemed to meander so aimlessly and conclude in such a random way: the Times simply isn’t good at this kind of thing. Which is itself a good thing.

But after several further minutes of reflection, I noticed a much more specific problem with the piece: it is utterly stacked with anonymous statements and characterizations. To quantitatively confirm my suspicions, I re-read the article, this time marking every statement by any source (including quotes, paraphrases, and descriptions) that met the following criteria:

Keep in mind that these are extremely conservative criteria. There are, for example, multiple statements attributed to “several people close to Clinton,” “several people close to the Clintons,” “several others,” and “others,” to name a few examples. These I did not count, as it is conceivable that the sources’ collective anonymity was more a function of Chozick’s concision than her sources’ desire for discretion.

I was also, of course, careful to include all instances of named (that is, not anonymous) sources. Consider the following passage from the article:

A few months later, over lunch near the White House, Reines laughed as a couple of meddlesome emails popped up on his BlackBerry from two older Clinton loyalists who had re-emerged since she left State. In between bites of a shrimp cocktail, he called these noodges “space cowboys,” referring to the 2000 film in which Clint Eastwood, Tommy Lee Jones and Donald Sutherland play aging pilots who reunite to disarm a Soviet-era satellite on one last mission.

I counted this as a named statement, despite the fact that it’s only two words long (“space cowboys”). I’m also counting it as a separate named statement from another quote earlier in the same paragraph by the same source, solely because the statements occurred at different times chronologically. (Elsewhere, I counted him again in an innocuous comment about the names of his kittens.)

Despite all of these precautions, 18 of the 36 statements — exactly 50% — that were made to Chozick in the course of “Planet Hillary” were anonymous (19 of 37 if I’d counted “a foundation spokesman,” which didn’t seem designed to provide discretion, but rather to avoid introducing too many irrelevant names). Here were a few representative examples:

(Emphases mine. You can check my count by viewing my spreadsheet here. Yellow-highlighted rows represent anonymous statements.)

The “Guidelines on Integrity” document available from The New York Times Company’s web site has this to say about anonymous sources:

Anonymity and Its Devices. The use of unidentified sources is reserved for situations in which the newspaper could not otherwise print information it considers newsworthy and reliable. When possible, reporter and editor should discuss any promise of anonymity before it is made, or before the reporting begins on a story that may result in such a commitment. (Some beats, like criminal justice or national security, may carry standing authorization for the reporter to grant anonymity.) The stylebook discusses the forms of attribution for such cases: the general rule is to tell readers as much as we can about the placement and known motivation of the source. While we avoid automatic phrases about a source’s having “insisted on anonymity,” we should try to state tersely what kind of understanding was actually reached by reporter and source, especially when we can shed light on the source’s reasons. The Times does not dissemble about its sources does not, for example, refer to a single person as “sources” and does not say “other officials” when quoting someone who has already been cited by name. There can be no prescribed formula for such attribution, but it should be literally truthful, and not coy.

Similarly, The New York Times Manual of Style and Usage states:

[A]nonymity is a last resort, for situations in which the newspaper could not otherwise print information it considers newsworthy and reliable. Reporters should not offer a news source anonymity without first pressing to use a name or other helpful identification…

If concealment proves necessary, writers should avoid automatic references to sources who “insisted on anonymity” or “demanded anonymity”; rote phrases offer the reader no help. When possible, though, articles should tersely explain what kind of understanding was actually reached by reporter and source, and should shed light on the reasons. Anonymity should not shield a press officer whose job is to be publicly accountable. And, given the requirements of newsworthiness and substance, it should not be invoked for a trivial comment: “The party ended after midnight,” said a doorman who demanded anonymity. (If the doorman simply refused to give his name, that is a less grandiose matter, and the article should just say so.)

Anonymity must not become a cloak for attacks on people, institutions or policies. If pejorative remarks are worth reporting and cannot be specifically attributed, they may be paraphrased or described after thorough discussion between writer and editor. The vivid language of direct quotation confers an unfair advantage on a speaker or writer who hides behind the newspaper, and turns of phrase are valueless to a reader who cannot assess the source.

It is quite clear that the three nameless quotes I excerpted above, as well as others like them, fail to meet the Times‘ threshold for granting anonymity. In some cases, Chozick’s usage is directly contradictory to policy. If anonymity “should not be invoked for a trivial comment,” then the statement by the “one aide” (quoted above) on the size of Hillary Clinton’s Washington office, for example, is certainly a violation of the rule.

Anonymous statements have long been a source of contention with readers, a point Times public editor Margaret Sullivan has raised multiple times. (A 2009 article by a previous public editor for the Times, Clark Hoyt, cited a study finding that almost 80 percent of anonymous statements in the newspaper failed to meet the official New York Times standard.)

“Planet Hillary” seemed to me to be an especially egregious case, as the underlying substance of the article was already paper-thin. The anonymous statements simply added to the puffy feel of the piece itself and contributed to an overall sense of (mostly banal) palace intrigue. Here’s hoping to see less of this in the future.

Probably not, unfortunately. But it helps to have a counterweight, even one as fecklessly centrist as J Street. The relatively new “pro-Israel, pro-peace” organization (whatever that means) is urging Congress not to pass a new Iran sanctions bill. National Journal takes stock of the situation:

The rise of J Street, a younger pro-Israel lobby pushing hard against the new sanctions, is serving as a counterweight to AIPAC on this issue. Revived hope for a diplomatic breakthrough with new Iranian President Hassan Rouhani helps J Street’s cause. So does political pressure from Obama. By decoupling support for Israel with support for new sanctions against Iran, the group is making it easier for lawmakers inclined to support the White House.

“We’ve been working diligently on Capitol Hill and in the Jewish-American community to raise support for the president’s diplomatic efforts vis-a-vis Iran, and oppose any legislation which would threaten it,” said Dylan Williams, director of government affairs at J Street. “We feel very strongly that the current bill in the Senate would threaten diplomacy.”

J Street’s influence is also clear in the money it spends. Among pro-Israel groups, JStreetPAC was the largest single political donor during the 2008 and 2012 cycles, contributing nearly $2.7 million to federal candidates, parties, and outside groups.

Not so fast, says Foreign Policy:

A recent letter attacking Democratic National Committee Chairwoman Debbie Wasserman Schultz is causing an internal brouhaha at the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, The Cable has learned. The powerful lobbying outfit, known for its disciplined non-partisan advocacy for Israel, recently issued an action alert about the Florida congresswoman’s waffling on Iran sanctions legislation. The letter urged members to contact Wasserman Schultz and cited a disparaging article about her in a conservative website founded by a prominent Republican political operative.

That AIPAC was driving hard for new Iran sanctions legislation surprised no one. But its use of a right-wing blog to target a well-connected Jewish Democrat with a long history of support for Israel raised eyebrows among some current and former AIPAC officials. It also raised concerns that AIPAC’s open revolt against the White House’s Iran diplomacy could fray its relations with liberal Democrats on the Hill.

“In the 40 years I’ve been involved with AIPAC, this is the first time I’ve seen such a blatant departure from bipartisanship,” said Doug Bloomfield, AIPAC’s former chief lobbyist.

My inner optimist wants to believe this is the last, dying gasp of an organization desperately short on ideas. But then I remember that I live in the United States, and I laugh at my inner optimist.

Almost alone among the professions, journalism is not rooted in a body of substantive knowledge. The claim is not that journalists lack knowledge or skill, for that is far from true. Nor is the claim an entry into the perennial but ultimately fruitless debate over whether journalism is a craft rather than a profession. The claim instead is a precise one: Journalism is not grounded in a systematic body of substantive knowledge that would protect its practitioners’ autonomy and inform their judgment.

The above passage was penned by Thomas E. Patterson in his recent book, Informing the News: The Need for Knowledge-Based Journalism. I was reminded of it today after reading this on GigaOm:

If you were reading some of the major tech-news sites on Wednesday — including the New York Times and Washington Post tech blogs — you might have gotten the impression that a huge proportion of the Chinese internet somehow got redirected to a small house in Wyoming on Tuesday. Why? Because that’s what a lot of the headlines said. The truth is almost as strange, but a Chinese technical glitch plays the starring role in the story, not a small house in Wyoming.

The house that captured everyone’s attention is a tiny brick home on what looks like a well-manicured street in Cheyenne, Wyoming. It showed up in photos on Gizmodo and The Verge, under headlines like “Most of China’s Web Traffic Wound Up at a Tiny Wyoming House Yesterday” and “Chinese Internet Traffic Redirected to Small Wyoming House” (that one was the New York Times tech blog). The Washington Post said that “thousands if not millions of Chinese Internet users were being dumped at the door of a tiny, brick-front house.”

…

In fact, the small house is just the company’s registered business address, one that is used by thousands of shell companies and other corporations who want to remain relatively anonymous (and the company that registered it has actually moved to a different address in Wyoming). The traffic actually went to wherever Sophidea’s servers are located, which is hard to say with any precision.

Among many other things, the Edward Snowden story helped expose a woeful shortage of technical savvy among our national press corps. As the next generation heads to the blogosphere, here’s hoping these mistakes become fewer and further between.

I don’t make a habit of reading David Brooks anymore, so I suppose it’s no surprise that I didn’t run across yesterday’s piece until just now. It begins, “Tragedy has twice visited the Woodiwiss family,” a sentence that immediately piqued my curiosity. Years ago, I had a professor with the same peculiar last name. The next sentence, about the death of a woman named Anna after she’d been thrown from a horse, confirmed that Brooks was writing about the same family whose father had once taught my Political Philosophy class.

His name was Ashley. It was the fall of my sophomore year, and I was a typically heady student impassioned by the notion of political contrarianism generally and reactionary liberalism specifically. The school was Wheaton College, a devoutly evangelical institution perpetually toeing the border between extreme-right social ideology and academic mainstream respectability. (It succeeded brilliantly in the former arena and marginally less so in the latter.)

I was conflicted, born into a conservative family cursed (blessed, really) to settle in the Boston suburbs. Despite my considerable social isolation as a child, enough of that famed Northeastern elitist progressivism rubbed off on me to be viscerally repulsed by the ménage à trois of religion, academia, and Republican politics that permeated Wheaton’s classrooms and chapel halls.

Ashley Woodiwiss was a godsend, an embodiment of absurd contradictions. He had seven children, but was nevertheless a high-church Episcopalian in the decidedly low-church bastion of American Midwestern Christendom. He always opened his class with a reading from his pocket-sized Episcopalian prayer book, repeatedly joking that he had no idea how to pray without it. Even this self-deprecation transformed itself, to my impressionable ears, into a subtle mockery of his evangelical peers: their casual descriptions of alleged interactions with God as the laughable contrast to his distinctly Victorian bedside manner with the Almighty.

I loved him for other reasons as well. On the first day of the semester, he inquired as to whether any freshmen were present. Upon hearing nothing, he continued, “Good. Now I can cuss and tell anti-Bush jokes.”

That fall, the Democrats finally retook the House from the GOP, ending their twelve-year reign atop the chamber. This utterly delighted Woodiwiss. Beforehand, while jokingly previewing his upcoming behavior at the polling station, he told us he planned to ask an election official where exactly the “no-electioneering” line ended, step as close to it as possible, yell “Throw the bums out!” and then stride purposefully inside to cast a vote to do just that to the Republicans.

During another class session, he mused, “Jimmy Carter had Habitat for Humanity after he left office, Bill Clinton is a huge policy wonk now, so what’s Bush going to do? Speak to large churches?”

He assigned Shakespeare readings. Once, while attempting to show the class a production of one of the Bard’s plays on VHS (these were the old days, after all), he inadvertently switched the TV to a Manchester United game, whereupon he declared himself “morally torn” and proceeded to watch for several more minutes.

I remember, finally, a game he used to play on Mondays. “I want to hear three stories from this weekend where you remembered you go to Wheaton,” he’d say. A student would call out, “I went to a twenty-first birthday party and no one was drunk.” Someone else might add, “The highlight of my weekend was finding hash browns in the cafeteria on Sunday morning.” “Fantastic!” he’d respond, practically giggling.

It was, indeed, moments like these that endeared him to me most. Reading back through emails I wrote to my family at the time, I’m a little taken aback to find my barely-exaggerated descriptions of him as, alternatively, “St. Ashley Woodiwiss” and a “demigod.” Hovering beneath the surface of my academic man-crush was my giddiness at feeling like an insider: I felt at the time as if I were the only student who truly understood his acerbic wit and, more importantly, was intellectually sophisticated enough to endorse his progressive politics and share his sarcastic dismissal of evangelicalism.

This was probably not perfectly accurate, of course. But reality felt sufficiently similar such that my enjoyment of his class owed at least as much to my fellow students’ imagined bewilderment at his antics as it was to the substance of the jokes themselves.

Years later, I ran into another former student of his, now knee-deep into the (smoldering ruins of the) conservative intellectual sphere. He kindly forwarded me some favorite Woodiwiss quotes he’d once compiled and sent to the professor. Reading them now, I’m almost shocked at their mundaneness:

It’s difficult to fully appreciate, over seven years later, what it was about this brand of humor that so captured me as a rapt 19-year-old. There is, moreover, an inescapable irony in the fact that I received this exhaustive list of Woodiwiss’ anecdotes from a very conservative classmate, an implicit rebuke of my longtime “insider” illusion. Indeed, given the benefit of hindsight, the quote that stands out most to me now is this one: “This is the Wheaton version of a liberal,” he said once. “At Chapel Hill I’m a fascist.”

He isn’t wrong. There was little truly radical about Ashley Woodiwiss. Stripped of any context, his ironic musings were red meat to malleable students craving brain food. But despite their appearance in his Political Philosophy class, these quotes were neither political nor philosophical in essence.

In David Brooks’ piece, which discusses the death of one of Ashley’s daughters and a serious injury to another, Woodiwiss speaks of lessons learned. “Ashley also warned against those who would overinterpret, and try to make sense of the inexplicable. Even devout Christians, as the Woodiwisses are, should worry about taking theology beyond its limits. Theology is a grounding in ultimate hope, not a formula book to explain away each individual event.”

It’s not a direct quote, but I’ll take it. It sounds like something my old Political Philosophy professor might have said. Right before trying to convince everyone that George W. Bush was the worst American president of all time.