McCullen v. Coakley has received a good deal of attention in the press already because of its contentious subject matter: anti-abortion activists are challenging a 2007 Massachusetts statute that created 35-feet “buffer zones” around the entrances, exits and driveways of all reproductive health care facilities in the state, arguing that the law infringes upon their First Amendment rights to share their views in a public forum. Due to personnel changes, there is a very good chance that the Supreme Court will end up overturning its own thirteen-year-old precedent in order to invalidate the Massachusetts law. But just in case you needed another reason to follow the oral arguments for McCullen v. Coakley tomorrow, here’s one more: even though the case has zero bearing on the constitutionality of abortion, Justice Scalia is going to give us some choice quotes railing against Roe v. Wade and the Court’s abortion jurisprudence.

Why do I think this? Just look at Justice Scalia’s dissent in Hill v. Colorado, the 2000 case that the anti-abortion activists in Massachusetts are asking the Supreme Court to overrule. In Hill, six justices (Chief Justice William Rehnquist and Justices Stevens, O’Connor, Breyer, Souter and Ginsburg) voted to uphold a Colorado law that was similar but arguably posed even less of a First Amendment problem than the Massachusetts law now in question: Colorado’s statute created a buffer zone of only eight feet, and it applied to all health care facilities. Writing for the majority, Justice John Paul Stevens balanced anti-abortion protestors’ right to free speech against the “recognizable” privacy interests of the “unwilling listener” and came out in favor of the latter. Stevens reached back into a 1928 Court opinion by Justice Brandeis for “the right to be let alone” from unwelcome speech and ran with it, concluding that Colorado’s interests in protecting patients and staff members from impeded access to the facilities and the content-neutral way in which the law was written satisfied the First Amendment.

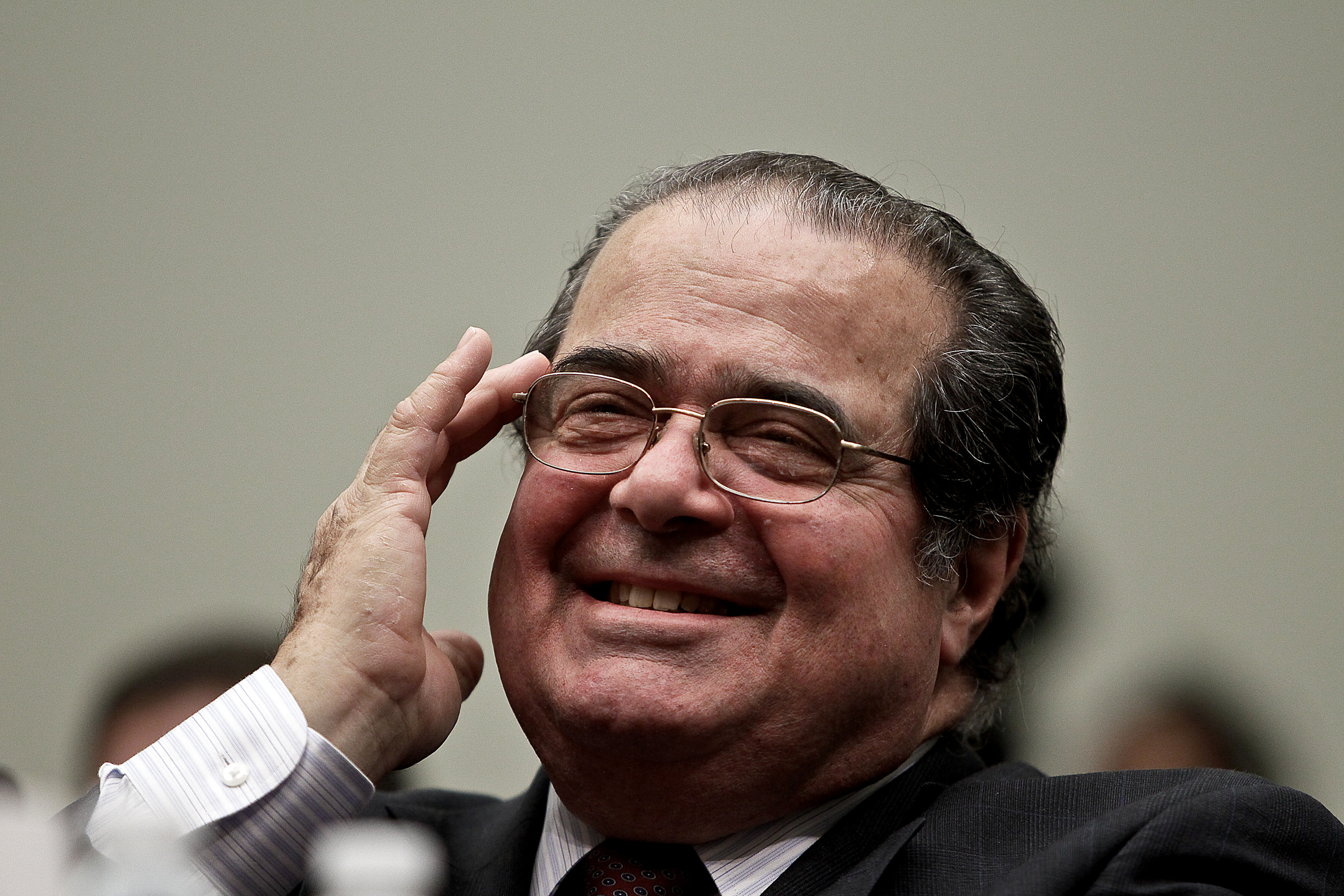

Justice Scalia was livid. His dissent, which Justice Thomas joined (but not Justice Kennedy, who wrote his own separate dissent, for reasons that are obvious once you read the two), is vintage Scalia in its mix of anger, indignation and sarcasm. In my view, he quite effectively calls out Justice Stevens’ shaky reasoning regarding the unwilling audience, pointing out that what Justice Brandeis actually meant was the “right to be let alone” by the government, not the right to be free from hearing other private speakers communicating their message in a public setting. Being Scalia, however, he doesn’t stop there. The First Amendment is not the only thing at stake. Justice Scalia wants you to know that the Hill decision is just one in a long line of animus-driven, unconstitutional attacks on the rights of the unborn and those who would save them, so he takes the opportunity to excoriate the Court’s “relentlessly pro-abortion jurisprudence:”

What is before us, after all, is a speech regulation directed against the opponents of abortion, and it therefore enjoys the benefit of the ‘ad hoc nullification machine’ that the Court has set in motion to push aside whatever doctrines of constitutional law stand in the way of that highly favored practice [citation omitted]. Having deprived abortion opponents of the political right to persuade the electorate that abortion should be restricted by law, the Court today continues and expands its assault upon their individual right to persuade women contemplating abortion that what they are doing is wrong.

The emphasis is mine.

The public forum involved here–the public spaces outside of health care facilities–has become, by necessity and by virtue of this Court’s decisions, a forum of last resort for those who oppose abortion. The possibility of limiting abortion by legislative means–even abortion of a live-and-kicking child that is almost entirely out of the womb–has been rendered impossible by our decisions from Roe v. Wade… For those who share an abiding moral or religious conviction (or, for that matter, simply a biological appreciation) that abortion is the taking of a human life, there is no option but to persuade women, one by one, not to make that choice. And as a general matter, the most effective place, if not the only place, where that persuasion can occur, is outside the entrances to abortion facilities.

And in the final paragraph:

Does the deck seem stacked? You bet. As I have suggested throughout this opinion, today’s decision is not an isolated distortion of our traditional constitutional principles, but is one of many aggressively proabortion novelties announced by the Court in recent years.

Look for more of these quotable “suggestions” from Justice Scalia tomorrow, the incidence of which is only made more likely by the fact that this time around, with Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Alito on the bench, he will likely have enough votes to jettison Hill once and for all. Justice Kennedy may well end up writing a final opinion in McCullen that is based on his own Hill dissent–a much more temperate disagreement that skipped the “proabortion” talk and stayed focused on the First Amendment–but Scalia will doubtless take this opportunity to run a victory lap.