The AL East-leading Red Sox (haven’t seen those words in a row anytime lately, have you?) head into their home opener this afternoon with a record of 4-2. It’s Clay Buchholz vs. the Baltimore Orioles’ Wei-Yin Chen at 2:05 PM EST.

Redemption time.

The AL East-leading Red Sox (haven’t seen those words in a row anytime lately, have you?) head into their home opener this afternoon with a record of 4-2. It’s Clay Buchholz vs. the Baltimore Orioles’ Wei-Yin Chen at 2:05 PM EST.

Redemption time.

I’d be lying if I said I didn’t find this at least a little charming.

I’ll admit it: I’m procrastinating again. But what of it?

So here’s what I’ve done. I took the game logs for the 2012 season and removed all intra-divisional matches. So out of the 2,430 games played last season, this left 1,358 games — all of them played between teams from different divisions.

Then I totaled up the collective wins for all teams within each division — again, excluding games played against each other — and came up with winning percentages for each of the six divisions. Here’s how it panned out:

AL West: 237-183 (.564)

AL East: 240-210 (.533)

NL East: 236-214 (.524)

NL West: 221-229 (.491)

NL Central: 225-271 (.454)

AL Central: 199-251 (.442)

I have yet to look into these figures on a historical continuum, but I’m guessing it’s a rarity for the AL East (traditionally thought of as the toughest division in baseball, at least for some time now) to be knocked off its perch at the top.

Anyone have a better way of measuring division strength? I’ve seen some articles written over the past few years that count all postseason series won (or even participated in) by teams from the various divisions. But since postseason success is partially determined by how a team performs within its own division, I’m not convinced that counting postseason series is the best way to measure division strength — especially given baseball’s disproportionately intra-division game schedules. Team performances against division rivals should be discounted from evaluations of overall division strength.

Unless I’m missing something?

Matthew Leach, writing for MLB.com, notes the recently emerging unpredictability of the American League East:

The division that set the standard for sameness is virtually unrecognizable these days.

Just a decade ago, the American League East race was the most predictable competition in sports. From 1998 through 2003, the five East teams finished in exactly the same order, every single year. Six straight seasons with the Yankees on top, the (Devil) Rays on the bottom, and the Red Sox, Blue Jays and Orioles in order in between. It was baseball’s version of a caste system…

As the 2013 campaign approaches, though, that predictability is gone. Last year offered a taste, but this year might bring full-on chaos. And that’s great news — unless you’re a Yankees fan.

All five teams could finish in different positions than they did a year ago. Every club in the division has reason to think it can finish first. Every team in the division has reason to fear a flop. You want wide-open? You’ve got it.

Chris Lund, who wrote about this same phenomenon last December for The Hardball Times, was on the same page:

The Yankees and Red Sox both appear to be very expensive, mortal teams. The Tampa Bay Rays have several question marks on their roster. The Toronto Blue Jays have completely overhauled their roster, though how it will play out on the field remains to be seen. The Baltimore Orioles have stood pat thus far after a dream season one year ago.

The AL East seems as wide open as ever. Five teams are roughly capable of competing with one another, though many would score the Rays, Jays and Yankees as the favorites to come away with the division crown. Yet, with so much parity in the “toughest division in sports”, there has never been more reason to feel that the AL East has wandered into vulnerability.

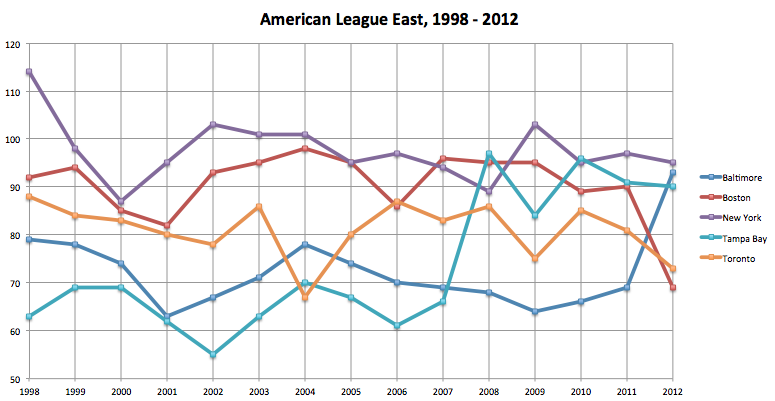

The graph above tells the story. The biggest season-over-season improvement for any one team in the AL East over that 15-year period was that of the Tampa Bay Rays from 2007 to 2008. Not only did they improve from 66 to 97 wins — an astounding 31-win jump — but they literally changed their name as well. (In 2007, they were the Tampa Bay Devil Rays. The next year they became the Tampa Bay Rays.)

As for the single biggest drop, that dubious distinction belongs to my beloved Boston Red Sox, whose collapse this past year — 69 wins, versus 90 in 2011 — was really just a continuation of the disaster begun in September 2011.

Zooming out to include all Major League Baseball teams, I’ve analyzed every year-over-year win differential since 1996/1997. (Although the current divisional format began in 1994, both that season and the subsequent one were shortened by the infamous strike.) The largest change in win total from one year to the next took place from 1997 to 1998, when the Florida Marlins’ record plummeted from 92-70 in their sophomore year to 54-108 the next season. Going in the other direction, the 1999 Arizona Diamondbacks improved on their 1998 total by 35 wins, jumping from an abysmal 65-97 record in their inaugural year to 100-62 in the followup.

The 2007/2008 jump of 31 wins for the Tampa Bay (Devil) Rays is second only to that leap by the Diamondbacks, going all the way back to 1996/1997 (a period that encompasses 506 entire team-seasons). Conversely, it provides me only a modicum of relief to note that the 2012 Red Sox’ 21-win dip is only bad enough to tie for 16th-worst year-over-year decline in that period — along with the 2002 Chicago Cubs (2001: 88-74; 2002: 67-95) and 2012 Philadelphia Phillies (2011: 102-60; 2012: 81-81).

Let’s just say I’m looking forward to putting all of this behind us for 2013. Oh, and go Red Sox.

From Baseball Prospectus 2013, page 53:

[The 2012 Boston Red Sox] missed 1,587 man-games to injury, second most of any team since 2007, as far back as our data goes. We estimate those injuries cost Boston 7.9 WARP [Wins Above Replacement Player], the most in baseball by 1.4.

Over at the web site, guest writer John Paschal takes a crack at why baseball players get injured so often, and in such bizarre fashion:

So, given the fact that objective math provides only an incomplete answer, we must turn to the subtle art of subjective guessing, with each of us hazarding a sound hypothesis as to why baseball players seem to suffer a disproportionate number of very odd mishaps—the sort that saw former infielder Chris Brown miss time because he “slept on (his) eye funny” and former infielder Geoff Blum land on the DL with an elbow injury he sustained while putting on a shirt. And let’s not forget the time All-Star Ron Gant, just a week after signing the largest single-season contract in history, broke a leg in an off-season motorcycle accident, or the day All-Star Larry Walker separated his shoulder while fishing.

“I’d say the reason baseball players injure themselves in weird ways is because they (a) have a lot of free time; and (b) they have a lot of money,” posits baseball writer Craig Calcaterra, of the NBC Sports website Hardball Talk, in an emailed response. “This allows them to fill that free time with all manner of fun and, occasionally, dangerous activities. Helping things along is that, as elite athletes, they have never had a particularly hard time doing things most people can’t do. I have this feeling a lot of them think they’re going to be immediately and effortlessly successful in other pursuits as well. Which, unfortunately, isn’t always the case.”

John Thorn, the Official Historian of Major League Baseball, is considerably more succinct.

“Randomness,” he writes.

Yes, it’s that time of year: I’m geeking out about baseball again.

…the Major League Baseball postseason (complete with two new playoff wildcards this year) has been a smashing success so far, proving once again that baseball is the greatest sport in the world. (And yes, that is an objective fact.)

Last night, the St. Louis Cardinals stunned the Washington Nationals in Game 5 of their National League Division Series to move on to the Championship Series. ESPN’s Jayson Stark is wowed:

These Cardinals keep doing it, all right. Like no one else has ever done it.

Twelve months ago, they went into the ninth inning of Game 6 of the World Series, trailing 7-5, and won. Friday night, they went into the ninth inning of a win-or-go-home Game 5 of the NL Division Series, down 7-5 again, and won. Again. Seriously.

You decide which of those reincarnations was more incredible, more impossible: Down to their last strike of the World Series in back-to-back innings? Or trailing by six runs ON THE ROAD, with a guy who might win the Cy Young (Gio Gonzalez) on the mound?

Keep in mind, before you answer, that in the 109-year history of postseason play, no team had fallen more than four runs behind in a winner-take-all game and come back to win.

Also keep in mind that only one team in postseason history — the 1992 Braves, in the legendary Francisco Cabrera Game — had trailed by two runs or more in the ninth inning of a winner-take-all game and roared back to win.

And, finally, keep in mind that only four teams had ever trailed by six runs or more at any point in any postseason game and found a way to win.

Until this game. Until Friday night in our nation’s capital. So you could make an excellent case that it was this game, in Nationals Park, that topped that game 12 months ago — yep, even a World Series elimination game.

The Nation‘s Dave Zirin is livid about Nationals general manager Mike Rizzo’s decision to shut down ace Stephen Strasburg when they needed him most:

I have no problem with caring about his health. I do have a problem with the Nats tanking this season out of arrogance and the media whipping a new, unsteady, colt-like baseball fan base into going along with the ride.

The baseball post-season can be an unpredictable, mind-bending experience where, as the Nationals found out, having the opposition down to its last out or even last strike doesn’t mean a thing. It’s a time when leaving a team—especially a veteran, resourceful team like the Cardinals—even a pinhole of oxygen can lead to a cascade of horror. The only truism in post-season baseball is that an ace pitcher, like some kind of Gandalfian wizard, can conquer all the dark magic the postseason can conjure. We saw this in Detroit series where defending Tigers Cy Young winner Justin Verlander shut out the pixie-dusted Oakland Athletics in their decisive Game 5. It happened in New York, where the great C.C. Sabathia broke the will and the bats of the fairy-tale Baltimore Orioles in their Game 5. Stephen Strasburg is DC’s Verlander, DC’s Sabathia. His moment was Game 5. Mike Rizzo took that away from this fan base. He took it away from a city that had poured $1 billion in public money into Nationals Park. He took it away from a team that showed all season that this could have been their year.

Rizzo, Boswell and all those who defended this decision should have the courage and the sense of shame to say that they were dead wrong. The true legacy of the Strasburg shutdown was shutting down an unforgettably beautiful season, leaving a legacy that tastes worse than chewing on dry aspirin. The arrogance of management and an unquestioning local media: it will get you every time.

Thomas Boswell’s column here. Key quote: “So all of the pundits who say the Nats can’t go to the Series or even win it, just because they won’t have Strasburg, can kiss my press pass.”

As Rick Perry so eloquently put it, oops.

As well he should. The knuckleball is a strange and beautiful pitch that also seems to play an outsized role in the imagination of baseball fans.

I’ll never forget Game 7 of the 2003 American League Championship Series. It was the worst sports moment of my entire life. And it wasn’t Tim Wakefield’s fault.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LGtpS1nJluE]

…I have to gloat about the only thing going right for my first love, the Boston Red Sox, this year:

Ten years ago, when the Boston Red Sox were sold to a trio of out-of-staters, the new owners signed a contract with state Attorney General Tom Reilly, promising to raise $20 million for area charities over 10 years. Soon after acquiring the team in February 2002, they established the Red Sox Foundation to fulfill that duty.

A report released Monday by the foundation reveals that it has donated more than twice that amount — a total of $52 million to charitable programs in the past decade — making the Red Sox by far the most charitable team in Major League Baseball.

The report offers a rare bit of good news for a team that has struggled all season, hovering at or near last place in the AL East standings.

Very rare indeed.

For those of us who measure the passing of time by the first pitch of successive baseball seasons, our annual celebration is now upon us. Tonight, the boys of summer return. Even better for those of us who plead allegiance to the vaunted red B, they will descend upon Fenway Park in Boston, where the hometown Red Sox host the World Series champion New York Yankees. (My fingers nearly mounted a mutiny as I finished typing that sentence.)

With a pitching rotation that includes newcomer John Lackey, Josh Beckett, and Jon Lester as the first three starters, the Sox are looking to be a team of solid defense and great pitching. For the first time in recent years, however, Boston’s lineup is looking vulnerable. We’ll need either a few career performances from unexpected players, a major acquisition sometime prior to the trading deadline, or both. For many years, the Sox used to be a team built to make it to the playoffs but without the depth to last once they got in. This year they may have the opposite problem.

Tonight, at 8:05 PM, be near a TV. Josh Beckett. C.C. Sabathia. Red Sox-Yankees at Fenway Park. And happy new year.