Tag Archives: Boston Marathon bombing

The bombing backlash, and a false equivalence

Jonathan Chait recaps the checkered performance of the media and the public in the Boston marathon bombing story:

In polarized America, both the reds and the blues have legitimate reason to fear that a tragedy will unleash an overly broad backlash. Liberals recall the false blame heaped on Muslim terrorists after Oklahoma City, and the real blame of 9/11 transforming into a fever of Bush-worship and jingoism. Conservatives recall mainstream reporters rushing to blame them, falsely, for shootings in Aurora and Tucson. It is also true that many Americans are eager, in senseless and fearful situations, for confirmation that the particular evil on display is the brand that conforms to their particular worldview. On Monday, there was comfort for some in the idea that the bombing was an act of tea-party loonies looking to exploit tax day. Among that same cohort was relief when the first pictures of the Tsarnaevs were released: The suspects were white, not Arab—maybe they were just another set of crazed teens with access to firearms. All week, nearly everyone was in a frenzy to profile, even those who should have known better.

There’s just one problem with this analysis: the consequences of misidentification are disproportionately stacked on one “side.” After the Oklahoma City bombing, the arrest and eventual execution of Timothy McVeigh had relatively little impact on American foreign and domestic policy. Sure, security was beefed up around federal buildings and other areas of interest, and President Bill Clinton attempted to leverage the attack into increased government powers, but life mostly went on.

Even after Aurora and Tucson, no one was rushing to strip conservatives of their legal rights, to surveil them more intensely, or anything else of the sort. Even if the killers had been conservatives, the most that liberals could’ve achieved is to point out (quite fairly) that conservatives can be just as extremist and violent as liberals (or liberals’ perceived “allies:” more on that in a moment).

Take, for example, the Norwegian massacre in 2011. Much of the American media rushed to broaden the scope of the gruesome attack, speculating immediately that the perpetrator was Muslim and, in so doing, implicating an entire religion. When it turned out he was a Christian conservative extremist instead, the cacophony of media bloodlust and anti-Muslim vitriol dwindled to mere whispers, the target of public anger was narrowed to a single man, and familiar defenses were trotted out: he was a lone madman, he didn’t represent any group other than himself, etc. These are, of course, sentiments not afforded Muslims and Arabs very often by these same publications.

There are, in other words, very light societal consequences for terrorism committed by ideological neighbors of the American conservative spectrum. But how quickly the tables turn when the suspect is a Muslim. (This is, in itself, an irony: nothing about fundamentalist Islam is remotely linkable to conventional liberalism, whereas fundamentalist Christianity is a crucial element within American conservatism. Islamic fundamentalism is, in fact, a much closer cousin of its Christian counterpart than it is of American progressivism.)

When the suspect is a Muslim, the consequences tend to be far greater and the overreactions more severe. September 11th, via a combination of mass hysteria, presidential incompetence, and public geopolitical ignorance, became a clear example of the catastrophe that can be unleashed on people-groups even in countries completely unrelated to the attacks.

A similarly frenzied dynamic is already enveloping the Boston Marathon bombing suspects, in some quarters. None other than U.S. Senator Lindsey Graham began publicly advocating the denial of basic rights to Dzhokhar Tsarnaev yesterday (a plea that was eventually successful, using a controversial “public safety” measure):

If captured, I hope Administration will at least consider holding the Boston suspect as enemy combatant for intelligence gathering purposes.

— Lindsey Graham (@GrahamBlog) April 19, 2013

The last thing we may want to do is read Boston suspect Miranda Rights telling him to "remain silent."

— Lindsey Graham (@GrahamBlog) April 19, 2013

The least of my worries is a criminal trial which will likely be held years from now. #Boston

— Lindsey Graham (@GrahamBlog) April 20, 2013

The Law of War allows us to hold individual in this scenario as potential enemy combatant w/o Miranda warnings or appointment of counsel.

— Lindsey Graham (@GrahamBlog) April 20, 2013

The goal is to gather intelligence and protect our nation which is under threat from radical Islam. #Boston

— Lindsey Graham (@GrahamBlog) April 20, 2013

The questioning of an enemy combatant for national security purposes has no limit on time or scope.

— Lindsey Graham (@GrahamBlog) April 20, 2013

Indeed, Graham, joined by Senators John McCain and Kelly Ayotte, as well as Representative Peter King, released a statement imperiously deeming Tsarnaev a “good candidate for enemy combatant status” and concluding:

We hope the Obama Administration will consider the enemy combatant option because it is allowed by national security statutes and U.S. Supreme Court decisions.

We continue to face threats from radical Islamists in small cells and large groups throughout the world. They have, as their primary focus, killing as many Americans as possible, preferably within the United States. We must never lose sight of this fact and act appropriately within our laws and values.

Even seemingly unrelated public policy issues are coming under fire as a “result” of the Boston Marathon bombing. See this piece from today, for example:

Opponents of immigration reform — the most promising priority of Obama’s second term remaining after the defeat of gun control — are already using the attack to try to slow progress on a bipartisan Senate bill.

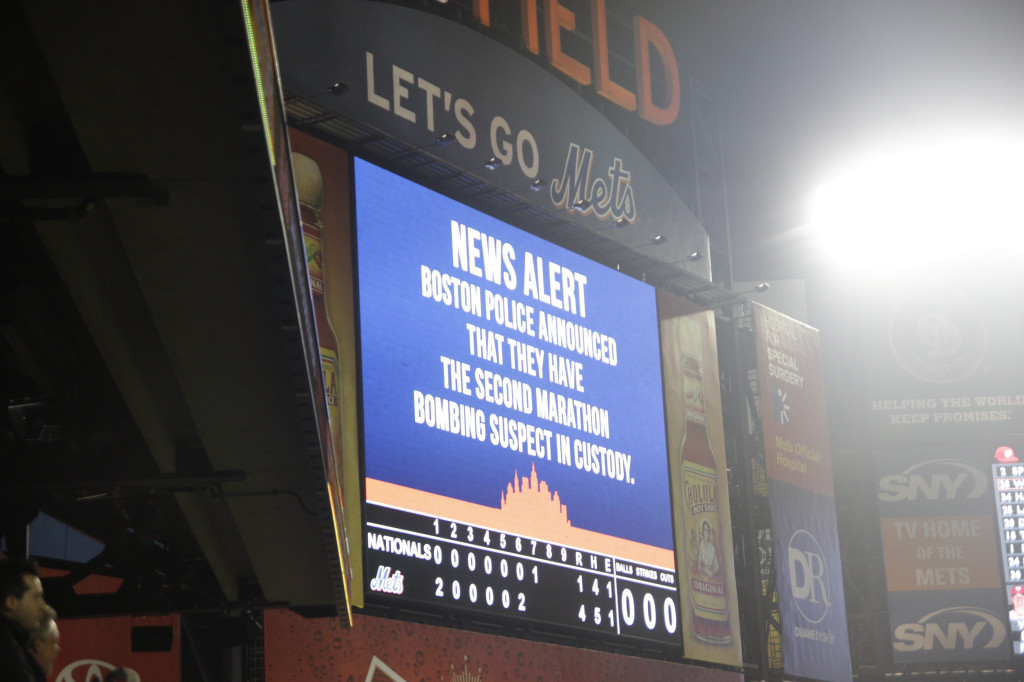

More broadly, the attack is raising questions about how the administration should deal with 19-year-old Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, who was captured Friday after an exhaustive manhunt in Boston, and concerns over whether the FBI was too complacent in letting his older brother Tamerlan Tsarnaev out of its sight after interviewing him in 2011.

So yes, it is true that, once the initial shock of the tragedy itself has been absorbed, both liberals and conservatives begin wincing at the possible fallout depending on who committed the crime. But as we have learned well over the years, public policy changes most when the suspect is part of a group used as a favorite conservative punching bag (in this case, Muslims). When the suspect is in any way connected to conservatism, the consequences are virtually nonexistent.

Related articles

Running from terror in Boston

http://twitter.com/rolldiggity/status/323888998558867456

On the third floor of the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism is the Pulitzer World Room, a mid-sized chamber that could easily double as a church sanctuary. Today, at around 2:30 PM, I arrived there to cover the official announcement of the Pulitzer Prize winners that was scheduled to take place at 3 PM.

After setting up with my computer, camera, and obligatory coffee, I began scanning TweetDeck, trying to find which hashtag was associated with the event and generally catching up on news. At around 2:51 PM, I ran across this tweet:

Two huge explosions just went off at #bostonmarathon finish. Cops running.

— Will Ritter (@MrWillRitter) April 15, 2013

At the time, it seemed out of place in my newsfeed, but it quickly became apparent just how relevant it was. Within minutes, a torrent of reports began flooding my computer screen in 140-character increments.

As it turns out, few places are more depressing than Twitter in the aftermath of a tragedy. What remains for most sentient human beings an unalloyed catastrophe that is mourned in solidarity with its victims requires all of thirty seconds on Twitter to devolve into a circus of self-righteous finger-wagging.

Of which I, like so many others, played my part. And yet there were so many aspects of today’s perfect Twitter storm that were so enraging in their lack of imagination and their utter predictability that it all felt, somehow, as if it were too much to handle at once.

I am from Boston (Everett, more precisely), and — like all Bostonians — have walked down Boylston Street far too many times to remember. Patriots’ Day is really, in the end, about two things: morning baseball and the Boston Marathon. Drinking plays a large role in both, and that is that.

And so part of my disbelief at the initial reports stemmed directly from the fact that a bombing in my hometown seemed so surreal, so otherworldly, so impossible, that it couldn’t have actually happened. I tried getting through to my parents and my little sister and kept bumping up against voicemail messages, endlessly ringing phones, and the even more ominous technical messages informing me the call could not be connected “at this time.” Eventually, I discovered none of them had even been in Massachusetts that day, let alone at home in Boston. But the horror remained.

There is a natural coming together after a tragedy. But even within this organic human impulse are concentric circles, ever-widening (or ever-narrowing, depending on the perspective) to include various scopes of “there”-ness. On September 11th, all Americans felt like New Yorkers. And all New Yorkers felt as if they had been at Ground Zero.

In reality, some people actually were there. Then, these geographical distinctions seemed not to matter. But today, there appeared to be a self-sorting taking place: the Bostonians versus the non-Bostonians, the true mourners versus the politicizers, those who demonstrated online “tact” versus the opportunists, and so on.

And yet we were all opportunists. If nothing else, today reminded me of how enormously petty people can be, as an actual human calamity was subsumed online under a wave of concern trolling and one-upsmanship. I don’t mean to pick on any one person in particular — because there truly was an enormous number of people doing this today — but it just so happened that one particular tweeter was especially prolific in this regard:

http://twitter.com/SaraMorrison/status/323880863672709120

http://twitter.com/SaraMorrison/status/323881303307075584

http://twitter.com/SaraMorrison/status/323888982779916288

http://twitter.com/SaraMorrison/status/323924796918358017

http://twitter.com/SaraMorrison/status/323950201163354112

Again, my point is not to pick on Morrison, with whom I’ve briefly interacted on Twitter in the past without incident (is there such a thing as a Twitter incident? a Twitcident?). She’s just the one particular user handle I remember from a long day of staring at my computer screen. I normally find her quite interesting, which is why I follow her in the first place.

But tweets like the above, in which boundaries are quickly drawn and stakes are claimed to some online/virtual form of legitimacy or sensitivity are just…ridiculous. Similarly maddening (and yet entirely predictable) is the knee-jerk scouring for the nearest maniac to provide a useful unhinged quote:

http://twitter.com/zackbeauchamp/status/323904005384323074

Controversial group Westboro Baptist Church says it will picket funerals of those killed by Boston Marathon bombs.

— Matthew Keys (@MatthewKeysLive) April 16, 2013

Why do these people even matter? Coverage is exactly what they want, but it is not at all clear what they have achieved to deserve it.

One final complaint: the obsession with the word “terrorism.” Everyone seemed to be holding his or her breath, waiting for the magic “T word” to escape President Obama’s lips during his press conference: after he didn’t, the conversation on TV turned to why not, and the conversation on Twitter turned to castigating the conversation on TV. This entire succession itself played out like a tired TV sitcom, with all the characters playing to typecast without the faintest trace of irony. Indeed, as Nate Silver succinctly put it:

What matters: 1) who did it; 2) how they did it; 3) why they did it. What doesn't matter: what we call it.

— Nate Silver (@NateSilver538) April 15, 2013