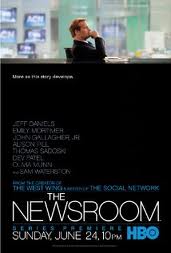

There was a moment in the second episode of The Newsroom where I really felt this series might pack a punch. Will McAvoy, the anchor of the evening news, is attending a brainstorming session led by his executive producer, MacKenzie, who rhetorically asks her assembled minions, “Are there really two sides to this story?” This wrinkles the fair brow of MacKenzie’s subordinate, Maggie, who asks, usefully, “What does that mean?” “The media’s biased towards fairness,” MacKenzie replies. To which Maggie rejoins, “How can you be biased toward fairness?”

There was a moment in the second episode of The Newsroom where I really felt this series might pack a punch. Will McAvoy, the anchor of the evening news, is attending a brainstorming session led by his executive producer, MacKenzie, who rhetorically asks her assembled minions, “Are there really two sides to this story?” This wrinkles the fair brow of MacKenzie’s subordinate, Maggie, who asks, usefully, “What does that mean?” “The media’s biased towards fairness,” MacKenzie replies. To which Maggie rejoins, “How can you be biased toward fairness?”

You get the point: this is Aaron Sorkin’s world, after all. Clueless women exist so five-minute expositional monologues don’t have to. (Even if recitations of entire Wikipedia articles, delivered hostage-style directly into the camera, would arguably be more realistic and less condescending.) Unsurprisingly, Will – imagine a leaner, meaner Jed Bartlet with a penchant for swearing because he has a show on goddamn, motherfucking HBO – has something to say:

“Bias toward fairness means that if the entire Congressional Republican Caucus were to walk into the House and propose a resolution stating that the Earth was flat, the Times would lead with, ‘Democrats and Republicans Can’t Agree on Shape of Earth.’”

With that decisive and sardonic blurt, The Newsroom caught my full attention. Unfortunately, it lost me a couple seconds later, when Sorkin’s cutely clever dialogue once again devolved into petty pitter-patter and destroyed any chance at genuine social commentary. Nevertheless, Sorkin’s thinly disguised nod to what NYU professor and media critic Jay Rosen has dubbed “The View from Nowhere” is worth further analysis.

In that fleeting moment, Will McAvoy’s brief diversion away from his Keith Olbermann-like self-absorption and into something a little more like media criticism got me fired up. I felt similarly while watching the premiere episode when, during a characteristically grating shouting match, MacKenzie demands of Will, “Where does it say that a good news show can’t be popular?” and he replies, “Nielsen ratings.” (As banal as these ideas may sound to anyone not living under a rock for the past few years, hearing them said aloud on a mainstream TV series was a little akin to reading Anderson Cooper’s coming-out email the other day: everyone knew it already, but it just hadn’t been said yet.) Perhaps this really was the series I’d been hoping The Newsroom would turn out to be when I’d first heard about it a couple months ago: a full-throated evisceration of fluff and reportorial false modesty disguised as “objective” news.

I really should’ve known better. To anyone who’s watched at least an episode or two of The West Wing, it is immediately clear that Sorkin desperately wants to believe in something. Problematically, he often explores this desire vicariously via nattily-attired male characters who passionately exchange juvenile tropes and platitudes, usually while striding briskly down a hallway, dodging Xerox machines and the occasional stray secretary. You can tell Sorkin feels a little sheepish about this boyish optimism, because – at least in The Newsroom, where a fleeting moment of cynicism occasionally breaks through his otherwise cloudy self-assurance – the character on the receiving end of the inspirational mini-speech often responds with just the sort of sarcastic aside Sorkin guesses a cynic might use.

But even this hedging of bets can’t dull the sharp edge off his innate bullishness on life: inevitably, the cynic is won over in the end – of the scene or the episode, never mind the season. I distinctly remember the final minutes of one episode of The West Wing (early in season two, I believe) in which most of the major characters are drinking beers on a brownstone stoop late into the evening. Josh Lyman is telling a story whose moral ultimately boils down to “America, Fuck Yeah,” and each of his enraptured listeners, speaking in solemn, hushed tones, responds in turn, “God bless America.” (“God bless America.” “God bless America.”) Ladies and gentlemen, Aaron Sorkin. So yes, while The Newsroom’s two main characters verbally bludgeon each other in the age-old fight between integrity and popularity, Sorkin long ago waved the white flag. Nielsen ratings, you see.

I bring this up because, providentially or otherwise, around the same time I first watched the pilot episode of The Newsroom, I’d also begun reading, at a friend’s recommendation, Neil Postman’s classic, Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business. Caveat: I’m still only a third of the way through the book, but that’s far enough along to help me start mentally tying a common thread that weaves together a mélange of seemingly disparate entities from Sorkinist idealism to Jay Rosen’s “View from Nowhere” to Ricky Gervais’ TV show Extras to New York Times public editor Arthur Brisbane’s confusion to, yes, Anderson Cooper’s sexuality.

Let’s start with Postman. In Amusing Ourselves to Death, he distinguishes between what he dubs “television’s junk” on the one hand versus what self-serving journalists might call “serious television” on the other. “I raise no objection to television’s junk. The best things on television are its junk, and no one and nothing is seriously threatened by it,” he reassures us, but then warns, “Besides, we do not measure a culture by its output of undisguised trivialities but by what it claims as significant.”

The question, then, is which category can most accurately lay claim to The Newsroom. I think I could venture an uneducated guess as to Postman’s take: whichever category doesn’t include the Lincoln-Douglas debates, for starters; whichever one does include TV shows about TV shows about the news, as a follow-up. Clearly, Sorkin and Postman wouldn’t see eye to eye on this (nor on anything else, most likely). On the one hand, Sorkin can easily be dismissed. No creator prefers to think of his invention as “television’s junk.”

On the other hand, a TV series that launches an honest attempt to take on the absurdities of its own medium warrants respect if executed correctly. I don’t watch a lot of television, but in terms of creating a legitimate space for introspection and self-reflection, it’s hard for me to come up with a better example than British comedian Ricky Gervais’ hit show Extras.

The first season, while hilarious, isn’t particularly notable on a deeper level, but it’s the second (and final) season that really turns the corner into a full-frontal assault on television entertainment. There must be no sweeter irony than pillorying BBC TV executives as slavish devotees of the almighty bottom line on a show financed and aired by that very same company. This was form making sweet, sweet love to content.

If, as Postman (himself paraphrasing Marshall McLuhan) postulates, “the medium is the metaphor,” then Gervais seemed to grasp this lesson perfectly. Season two is a six-episode marathon portraying the slow, tortuous disintegration of an aspiring artiste into a self-loathing puppet spouting catchphrases in a desperate, cloying attempt to placate his overlords and stave off the fast-approaching death of his TV celebrity. It’s a remarkably pathetic descent, rendered all the more so by the oddly moving spectacle of Gervais’ character clumsily pirouetting through increasingly incoherent rationalizations so as to shield himself from the reality of his self-annihilation.

And then, just like that, after twelve episodes and one Christmas special, Ricky Gervais and his brainchild, Extras, bowed out, almost assuredly leaving money on the table. Nothing more needed to be said. To do otherwise would have been to jeopardize the credibility of his critique and, paradoxically, would have turned his real-life series into a self-parody, life imitating art. No, then. Leave the sequels to pirates and superheroes.

It is against this mental backdrop of mine that Aaron Sorkin was unlucky enough to submit his latest entry. Reciting trite clichés in steady vocal crescendos makes for entertaining television. It may even make for great television. But great television – even the best thing on TV, Postman reminds us – is the junk. TV Sorkin-land occupies the world just a few ladder rungs above the tundra of laugh tracks and catchphrases, ambitious enough to fancy itself serious but oblivious beyond measure to its startling irrelevance. I can envision, sometime in 2020, a season nine where a thoroughly sincere Will McAvoy rails against the frivolous pursuit of Nielsen ratings and advertising dollars, and I can envision myself, years before, having thrown my remote control through the wall.

Even a show like Extras is probably not what Postman had in mind when he discussed the things “[a culture] claims as significant.” Indeed, his keen eye was trained on the news desk, the anchor’s chair, the endlessly scrolling ticker. This was then, and still is now, the domain of “Very Serious People” (to borrow Paul Krugman’s phrase). And yet television news today is dominated by uber-partisan hatchet men on the one side and self-described “neutral” journalists on the other. The former star in shows like CNN’s ill-fated Crossfire, while the latter’s considerable terror of accidentally importing facts into fully contrived controversies leads them to abandon the task altogether and question, instead, whether the presidential candidates prefer iPhones to BlackBerries.

This is exactly what Postman had feared in his worst dystopian nightmare. Invoking the dichotomously grim futures envisioned in 1984 and Brave New World, Postman wrote: “Orwell feared that the truth would be concealed from us. Huxley feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance. Orwell feared we would become a captive culture. Huxley feared we would become a trivial culture.”

By 1985, when Amusing Ourselves to Death was first published, Postman was convinced Huxley’s vision had carried the day. What he might not have anticipated at the time was the retrogressive effect TV news would exert even on its older counterparts. (Or maybe he did: again, I’m only one-third finished.) It’s no longer just CNN throwing out more election-night holograms while FOX and MSNBC exchange clumps of angry spittle. The disease has spread backwards, infecting the previously immune printed press.

Among its victims is none other than the Grey Lady herself, the New York Times. Its public editor, Arthur Brisbane, recently ignited an Internet firestorm with his sincerely-titled column, “Should The Times Be a Truth Vigilante?” The online response was rapid, voluminous, and overwhelmingly of one mind: thankfully, virtually everyone was incredulous that the question even had to be asked. Brisbane’s query was a classic embodiment of Jay Rosen’s “View from Nowhere:” assuming, sans verification, that every story has two equally valid sides. As The Newsroom’s MacKenzie rightly noted, some stories have five sides. Some have one. But simply serving as the court stenographer, which was bad enough in the pre-Internet era, isn’t being fair anymore. It’s being lazy. Mostly, it’s being scared.

To the Times’ credit, Brisbane is its public editor, meaning he operates independently of all other staff. But a brief skimming of an average day’s news coverage makes it immediately obvious that the problem is widespread. To use one infamous example from relatively recent history, the paper’s longtime refusal to use the word “torture” to describe waterboarding spawned so much criticism that a satirical web app calling itself the “New York Times Torture Euphemism Generator” sprung up: one could refresh the page to yield various phrases like “enhanced physical audits” and “elevated nipple scrutiny.” Ironically, the Times’ then-public editor’s official explanation for its linguistic aversion to “torture” inadvertently reinforced its critics’ justified perception as to the paper’s insistence on perpetuating false equivalencies: “The Times is displeasing some who think ‘brutal’ is just a timid euphemism for torture and their opponents who think ‘brutal’ is too loaded.” (Because waterboarding isn’t brutal if it’s done fewer than 183 times per person. Look it up.)

It is perhaps more interesting to imagine Neil Postman’s take on the Internet as it exists today. As early as 1995, in an interview with Charlene Hunter Gault on PBS’ NewsHour, Postman expressed his alarm at the then-novel idea of an “information superhighway:” “I often wonder if this doesn’t signify the end of any meaningful community life.” (In a twist he could easily appreciate, this very interview stands today as a testament to a bygone era, one in which in-depth discussions of theoretical import could be shown on national TV and people would actually watch.) He conceded the interactive nature of the Internet, which contrasted it from the passivity of watching television, but feared – accurately – that it would nevertheless lead to a surge in tribalism (foreshadowing Cass Sunstein’s “information cocoons”) and actually divide the global community while claiming to unite it. De-contextualization – the commodification of information as a standalone product, utterly divorced from personal or even local significance – was a primary concern of Postman’s. And that’s where we jump to Anderson Cooper’s sexuality.

As a preemptive disclaimer, I happen to like Cooper more than just about anyone else doing news on TV today. (Not counting Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert, who together represent a nearly perfect antidote to Postman’s disgust for trivialities masquerading as something culturally significant: Stewart and Colbert are cultural signifiers masquerading as triviality.) But this doesn’t alter the fact that the recent “news” of his homosexuality embodied the worst of everything about the entertainment conglomerate approach to TV news.

Cooper is, quite literally, a TV celebrity. He’s famous solely by virtue of his position as someone who appears regularly on TV. It’s notable to what extent that trajectory alone – from TV presence to fame, and not the other way around – so profoundly contrasts itself with the print press. How many people would recognize Bill Keller walking down the street? How about Jill Abramson? The medium of television made Anderson Cooper who he is, and so it is only fitting that his self-outing should light up the television and computer screens of people all over the world in return. That Anderson Cooper’s sexuality bears no personal significance for any of these people is completely missed in the rush to retell and re-tweet the “breaking news.”

This may look like a tempest in a teapot, except that human attention spans are finite containers. Spending time talking about Anderson Cooper’s sexuality necessarily detracts from the available time and mental effort required to understand something else that might have infinitely more personal relevance. Worse yet, it conditions us to start categorizing stories like these as “news.” Not only is information out of context now an acceptable subject of extended discussion, but the type of wonky dissection of media critiques that Postman had launched into with Gault in 1995 now seems strangely quaint, a relic of a simpler, more boring time. The financial troubles of many of our historical newspapers signal the emergence of a culture that’s moved on from the world of facts and figures and swept straight into a sea of colors and noise and lights. And tickers. Endlessly scrolling tickers.

Will McAvoy wasn’t wrong to locate the media’s failure in its inability to favor facts over a dubious balancing act that ignores the central issues. But Sorkin was wrong, for implicitly positioning The Newsroom as intellectually significant when, so far at least, it’s really nothing more than a very conventional sitcom. Nothing more than junk television. Which just might make it the best thing on TV.