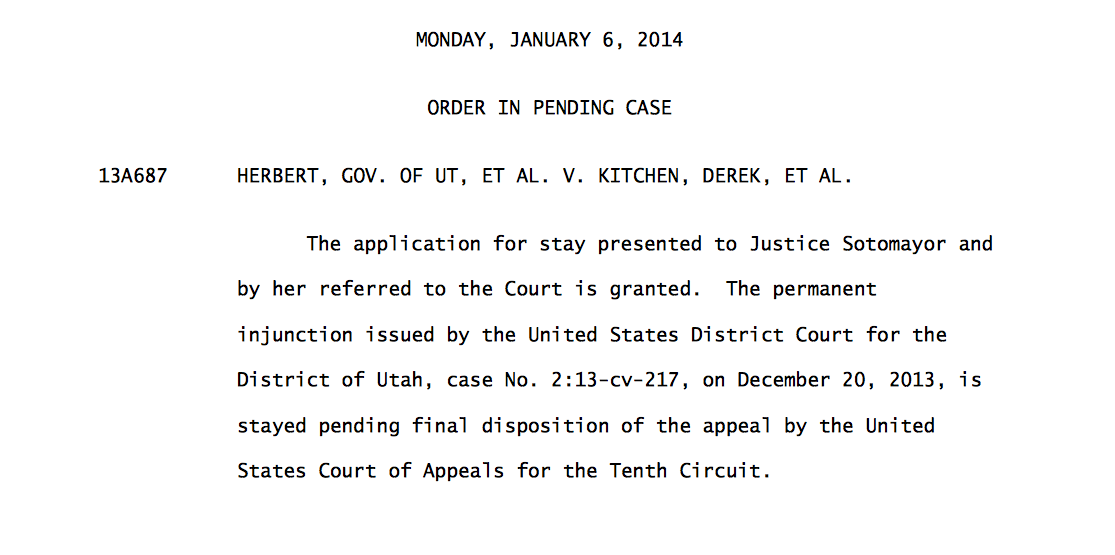

The Supreme Court pushed the “pause” button on gay marriage in Utah yesterday, preventing any new marriages between same-sex couples from taking place until the case has been decided on appeal by the Tenth Circuit. Let’s take a second to unpack the justices’ order:

OK, so there’s not a whole lot to unpack here. The grant indicates that Justice Sonia Sotomayor, the Circuit Justice in charge of handling stay applications arising from the Tenth Circuit, referred Utah’s request to the full court instead of deciding it herself. This was an expected outcome–as mentioned in my previous post explaining the stay application process, full-court consideration is the most efficient way to dispose of the request and prevent any “appeals” or resubmissions that could happen when an individual Circuit Justice rules on a stay. That the Supreme Court granted the stay was also not surprising. As Rick Hasen notes here, it was very likely that the Court (including even the justices who would support expanding same-sex marriage rights ((For an example of a Supreme Court justice advocating for an incremental approach to the recognition of a constitutional right, look no further than Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s comments on Roe v. Wade. She has repeatedly said that abortion rights should have been settled state-by-state rather than in one fell swoop, which in her opinion had the effect of polarizing the national discussion. A similar argument regarding strategy has played out amongst same-sex marriage proponents.)) ) would want to slow things down on such an important, far-reaching constitutional question.

So what does the grant yesterday tell us about how the Court may rule on the merits in Herbert v. Kitchen, when it is inevitably appealed from the Tenth Circuit? The answer is: very little. We do know that the Court will likely choose to hear the case–based on the requirements for successfully obtaining a stay (also detailed in the flowchart from my previous post), the Court would not have granted Utah its stay unless it thought there was a “reasonable probability” that four justices would grant certiorari when the case eventually winds its way up. We also know from the grant requirements that the full court thought there was a “fair prospect” that five justices might eventually overturn federal district Judge Robert Shelby’s ruling on the Utah same-sex marriage ban, probably because of his game-changing conclusion that same-sex marriage is a fundamental constitutional right–an issue that the Supreme Court itself assiduously avoided addressing in last year’s DOMA and Proposition 8 litigation.

Beyond these questions of probability, however, the grant itself contained no reasoning for the Justices’ decision and addressed none of the substantive arguments brought up by Utah and the same-sex couple plaintiffs, so it is hard to divine how they will rule on the merits. The criteria for granting a stay are different from the standards used for ruling on the substantive questions. The fact that it chose to hit the brakes on same-sex marriage in Utah now does not necessarily mean that the Court will strike down Judge Shelby’s ruling.

A more pressing question created by yesterday’s grant is what happens now to the 1,360 same-sex couples who received marriage licenses from the state–a majority of whom have already used the licenses to get legally married in the seventeen days before the Supreme Court halted the process. Interim Utah Attorney General Sean Reyes said in a press conference yesterday afternoon that he “doesn’t know.” These couples are in “legal limbo,” “uncharted territory.”

My personal feeling is that yesterday’s stay should not erase or invalidate the hundreds of same-sex marriages that were legally carried out in Utah in the period between Judge Shelby’s initial December 20 ruling and the Supreme Court order. Up until yesterday, while Utah’s stay request was slowly moving its way up the federal courts, Judge Shelby’s decision striking down Amendment 3 was still controlling in the state, so these marriages did not take place in violation of any court order or state ban. A trickier question is what happens to the couples who obtained marriage licenses legally during those seventeen days but had not actually gotten married by the time that the Supreme Court issued the stay. We should fully expect further “offshoot” litigation on this matter.

Finally, it’s worth noting that Utah is still weighing proposals to bring in outside counsel to help with Kitchen, which will be scheduled for argument before the Tenth Circuit this spring. Outside help would probably be a wise idea, given the state’s well-documented bungling in the last few weeks. That Utah dropped the ball repeatedly on moving its stay application along–first by neglecting to ask Judge Shelby at the litigation stage for a stay of any possible ruling in favor of the same-sex couples, then by running to the Tenth Circuit for an emergency stay before Judge Shelby had even ruled on its request, then by waiting a full week to appeal the Tenth Circuit stay denial to Justice Sotomayor–is the reason why the state is now dealing with such a large number of marriages that may or may not be legal.