I’ve long mounted a soapbox in defense of two related ideas. The first is that average Americans care less about policy specifics than we give ourselves credit for, and that public perception is defined more by soundbites, rhetoric, and presentation than by substance.

The second idea, which follows from the first, is that liberal politicians could — and should — mount a stronger defense of their policies without fear of reprisals from the conservative end of the spectrum. This is not because such reprisals won’t come — unless you’ve been in hiding since 2009, this has been the position of Congressional Republicans since Day 1 — but because holding to one’s principles in the face of political opposition is quite often perceived as indicative of having a better, more sensible policy.

To my endless blathering, you may now add the following academic paper:

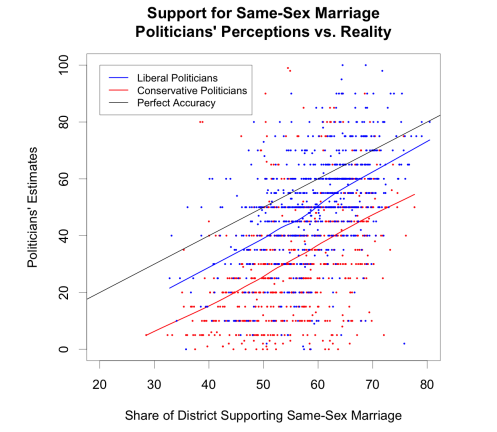

Broockman and Skovron find that legislators consistently believe their constituents are more conservative than they actually are. This includes Republicans and Democrats, liberals and conservatives. But conservative legislators generally overestimate the conservatism of their constituents by 20 points. “This difference is so large that nearly half of conservative politicians appear to believe that they represent a district that is more conservative on these issues than is the most conservative district in the entire country,” Broockman and Skovron write. This finding held up across a range of issues.

The authors conclude:

For those interested in strengthening democratic responsiveness, one tempting conclusion from this analysis is that alternative means of informing legislators about their constituents’ views need to be devised – democratic campaigns and elections appear to do little to update politicians’ perceptions of their constituents. However, on reflection, the fact that candidates and legislators know so little about their constituents and learn so little about them from campaigns and elections is perhaps indicative of a deeper and more basic problem of elite motivation. When Miller and Stokes (1963) conducted their authoritative study of information flows between representatives and their constituencies it was less clear how representatives might ascertain their constituencies’ views with a great deal of precision even if they so desired – reliable district-level opinion surveys were still relatively rare. However, if today’s elites viewed congruence with majority opinion as a primary goal we would expect considerably more knowledge of this opinion in our sample than we observe; such knowledge is quite inexpensive to obtain relative to the cost of modern campaigns. As with voters’ typically low level of motivation to learn about their representatives (Downs 1957, ch. 13), it thus appears that our respondents must have found little desire to accurately ascertain public opinion on political issues of the very highest salience. Politicians clearly do respond to cues about the political consequences of their actions when taking political positions (e.g. Kollman 1998; Bergan 2009), but accurately ascertaining the state of constituency opinion does not appear to rank fairly highly on their priorities necessary for gaining and maintaining access to political authority.

It’s simply too bad that there’s no institution designed to elucidate the opinions held by both the electorate and their chosen political representatives. An institution that could widely disseminate publicly relevant information on the vital policy issues of the day. An institution that would strip away the gratuitous sideshows, celebrity gossip, and tabloid fare, and focus instead on investigative reporting to enlighten its readers both within and without the halls of power.

We should build such an institution. And I propose we call it The Media.

(Thanks to Andrew Sullivan for flagging this one.)