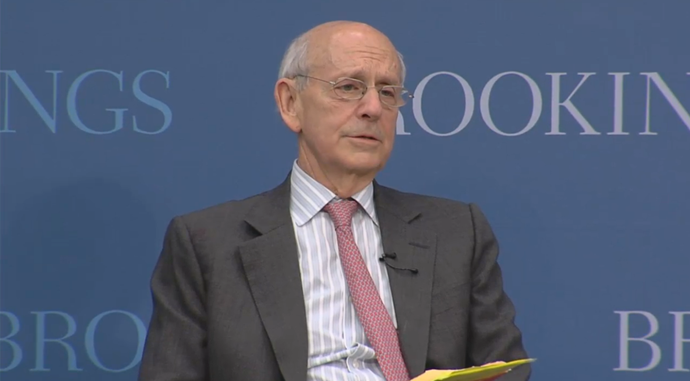

During the question-and-answer portion of Justice Stephen Breyer’s international law lecture at the Brookings Institution yesterday, an audience member from the Coalition for Court Transparency asked the justice about the possibility of live streaming audio from Supreme Court oral arguments. Justice Breyer gave a nearly six-minute reply which reiterated some of the same arguments he has made against live video in the past, but the answer did contain an interesting new tidbit at the end in which he mentions recent audio “experiments” from the D.C. Circuit.

Michelle Olsen of Appellate Daily published a transcription of the last part of this answer yesterday evening. The following is my transcription of the full question and answer, which I have slightly edited for clarity.

The relevant question starts at the 2:12:00 mark of the Brookings Institution video.

Audience Member: Alright, this is not a hot political question; it’s a hot legal question. My name is Karl, I’m with the Coalition for Court Transparency.

You referenced five areas [where] American judges might do well to consult foreign sources or foreign legal thought. High courts in Canada and the U.K. and many, many other countries have cameras.

I don’t want to know if you support cameras, because I already know where you stand on cameras in the Supreme Court–but there’s a nice lounge at the Supreme Court where Supreme Court bar members are allowed to listen to live audio. Why don’t we allow the live audio to be transmitted outside the building, to everybody else who might not have the money or means to come to Washington, D.C. and wait in line outside in the cold, [so that they can] listen to such audio?

Justice Breyer’s answer to this question begins at the 2:14:08 mark.

Justice Breyer: Now, to give my unsatisfactory answer to [the question] about cameras in the courtroom under the guise of radio, you have to understand that it’s a pretty tough question, and we’re pretty conservative–with a small “c”–when you start talking about our institution. I mean, we don’t know what would happen if we let cameras in the courtroom. And the risks would be–two [risks], and we don’t know what the answer is. Three [risks], actually.

One risk is that people would begin to think that the oral argument–which is about 5% [of what the Supreme Court does], almost all of our material is submitted in writing–they would begin to think that that was what we’re about. The oral argument! That would be misleading, but not deadly.

What might be worse is that people do relate to people. That’s good. You relate more to your family than you relate to your friends, than you relate to people you don’t know, and people you see you relate to more than people you just hear about, and statistics you relate to not at all. OK. That’s the human condition, and I think it’s probably a good one. But the job of an appellate court–and particularly our court, which is about three levels of appellate courts, or two–is to think about how our decision is affecting the 300 million people who aren’t in the courtroom. They’re not there. But they will possibly be affected by our ruling. And people might, well, just look–to the good guy and the bad guy. And that might have an impact on the effectiveness of the Court.

Or, what is the most obvious thing, and you get privately–opposite advice from different members of the press on this one. [Voices perspective of a SCOTUS justice] “It won’t affect us! I mean, we’re grown up, we hope. And there’s the press there anyway, And why will it affect what questions I ask? I have to watch what I say anyway!” Well, apparently, I don’t. But nonetheless, you have to watch it, it’s public and the press is there, so why would this make a difference? To which some members of the press will say, you just wait ’til you see how you react when you ask a question in good faith on A, and then it’s reported on various shows on television and they show a picture of you. You’ll be pretty careful, and maybe you’ll be careful to stop asking. That might be a public benefit, but nonetheless, you see the point. And you say, go see what happens in the Senate or the House, which perhaps has to respond to public opinion.

But the reason you have a court–the reason we decide constitutional questions–if you go back to Alexander Hamilton, is–why? Because this document [takes out pocket copy of Constitution]… it treats exactly the same way the least popular and the most popular person in the United States. That’s what it’s supposed to be. And by the way, he said, we better give the Court the power to review laws–why? Because if we give the President the power to say whatever he does is constitutional or not, he’ll always say it’s constitutional, and he has enough power already.

Why not give the power to Congress? After all, they’re elected, and many countries have done that. To which Alexander Hamilton says–he doesn’t say it in these words–he says, what happens when the decision is right but unpopular? He says, I’ll tell you about Congress–they are experts in popularity. He says, believe me, they know popularity. But what will they do when it’s unpopular? So let’s take these judges nobody’s ever heard of–they don’t have the power of the purse, they don’t have the power of the sword–fabulous. They’re weak. And give them the authority. And when it’s unpopular–unpopular and important, and by the way, possibly wrong–I mean, I’ve participated on both sides of 5-4 decisions. Not as many as you think–there may be 20% [of decisions that] are 5-4, 50% are unanimous–but somebody’s wrong in these cases. Alright, so–and that is the question I get from the President of the Supreme Court of Ghana, a woman who is trying to further democracy and civil, human rights in Ghana, and from Ouagadougou [in Burkina Faso], and from countries all over–why do people do what you say?

That’s a pretty good question. And it’s taken us–I say, there’s no answer in this document [the Constitution], and Hamilton didn’t answer it, either. He didn’t know. Nobody knew. It’s two hundred years of history. You want people in your country to follow courts and the rule of law–go out to the villages. Don’t just talk to the lawyers. Don’t just talk to the judges. By the way, there are in our country–contrary to popular belief–309 of the 310 million are not lawyers. Alright? And I say, they’re the ones that had to support sending the troops to Little Rock to enforce integration. They’re the ones that have to decide they will follow decisions that they think are really wrong and really unpopular. And that takes time. But that’s part of our job. And who knows? So I say we’re conservative with a small “c.”

And the radio? I mean, the radio–[unintelligible] they tried that in the D.C. Circuit [which has since September 2013 provided same-day audio for its oral arguments], didn’t hurt anything. Could we experiment with that? Maybe. But that’s not right in front of us. So therefore, that’s [my] not answering [the question].

—–

As mentioned in the beginning of this post, most of Justice Breyer’s answer, which focuses on insulating the Court from the misconceptions of the public, retreads his previous statements about cameras in the courtroom. In March 2013, in response to questioning from a House Appropriations subcommittee, Breyer mentioned the Court’s conservatism with a small “c” on the issue, the potential distortion by the press, and the self-censoring effects televised arguments could have on the justices’ questioning. He said then: “I’m not ready yet. I mean, I want to see a little bit more of how all this works in practice. I’d give people the power to experiment. I’d try to get studies–not paid for by the press–of how this is working in California, of how it affects public attitudes about the law. I’d like some real objective studies–I know that’s a bore, but that’s where I am at the moment.”

In January 2014, Justice Breyer told an audience at The Washington Center for Internships and Academic Seminars that he suspects it is a matter of when, not if, oral arguments are televised, but worried about the “demonizing and angelizing” of certain members of the Court.

What made yesterday’s answer different (and encouraging for advocates of live streaming) was his begrudging acknowledgment at the end that the D.C. Circuit has adapted its procedures to make oral arguments more accessible to the public, with no harm done to the integrity or the perception of the court. I would not go so far as to call it Breyer’s endorsement of live audio–as Michelle Olsen pointed out, the D.C. Circuit still doesn’t have live audio, only same-day audio, and it’s unclear which of these two practices Justice Breyer’s musings on “experiments” referred to. Given that the Supreme Court currently releases its argument recordings just once a week on Fridays, though, even moving toward same-day audio at One First Street would be a small step in the right direction.