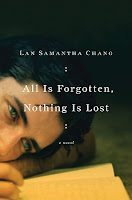

In All Is Forgotten, Nothing Is Lost, words occupy the highest rung on a ladder of competing interests. Author Lan Samantha Chang, director of the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop, vividly captures the artistic desperation and perfectionism that can lay waste to all other aspects of the life of a writer. Although recounted through the eyes of aspiring poet Roman Morris, the central figure is actually Miranda Sturgis, the seminar professor at “the School” whose classes “almost none escaped unaltered or unscathed” and whose legendarily harsh critiques of students’ work spawned the term “bludgeonings.”

And yet students, “[fearing] they had missed the age of poetry” (the year was 1986), inevitably clamor to enroll in Miranda’s classes, grasping desperately at salvation via literary osmosis. Bernard Sauvet, Roman’s fellow student and confidant — and, Roman decided, “one of the most serious poets in their class” — perpetually occupies himself with his poem about Wisconsin’s early exploration. Following a reading of the draft in class, Bernard is compelled by the seminar’s format to remain silent while his peers critique his work from contradicting angles: “The poem was overly lyrical; it was not lyrical enough. The poem did not reference history; it was too historical. The poem lacked essential irony; the poem was a farce.” When Miranda’s opinion is requested, she merely shrugs, shakes her head — “dismissing the poem, and Bernard, and possibly, thought Roman, all of them” — and states, “I think Bernard has heard enough today.”

To this, Bernard has only one reaction: “I think Miranda liked my poem,” he tells Roman. “Did you notice how she did?” Despite Roman’s attempts to manage his friend’s escalating expectations, Bernard nevertheless concludes that “we should think about what her indifference means…What might be learned from the indifference of a great poet.” It is this craving of Miranda’s attention that dominates the novel, a recognition, no matter how misplaced, that it is she alone who can rescue these would-be poets from the doldrums of their own mediocrity and earn them admission to the exclusive pantheon of literary greats. Roman, cynically refusing to read his poems in class until “he had assessed how his work would be received,” initially took an ambivalent perspective toward his teacher. “Was she indifferent to them, or was she guarding her privacy?” he wondered. “Was she cruel, or simply telling them the truth?”

When on the final day of class, Roman submits three poems — “powerful jigsaw pieces of an intimate world,” he is certain — for peer review, the critical response is less than extraordinary. Even Miranda notes, enigmatically, “In these poems, I find very little desire to speak of.” Just before dismissing the class, she concludes, “No one in the world is thanking you for being a poet.” Confronting her after class, Roman demands to know what she disliked about his poems, finally receiving the jarring reply, “You write as if you have no soul.”

What follows next is a series of events that first threaten and then obfuscate the line separating teacher and student, as Roman embarks on an unlikely relationship that is as future-less as it is extraordinary. Miranda, mentoring him in life as in poetry, spends countless hours toiling over his works with him until, at a graduation party on the semester’s last day, Roman reveals to Miranda his acceptance of a fellowship in California that will spell the end of their affair.

Chang’s narrative jumps forward immediately following this encounter. Roman is married (to a fellow graduate of the School) and has a child; he corresponds only sporadically with his formerly close friend, Bernard, and Miranda is largely a figment of a bitterly concluded past. Shortly after his time at the School, Roman was awarded a prestigious literary award for his first book of poetry, eventually earning him a professorship. But a stunning revelation regarding Miranda forces him to confront her in her office, in one of the most emotionally fraught moments in the novel. Roman’s relationship with Bernard, too, is later severed after a tense several months they spend under the same roof.

Everything, it seems, is sacrificed in pursuit of art, be it friends, spouses, or lovers. Looking at an old photograph taken the day of his graduation from the School, the older Roman marvels at his younger incarnation: “an absolutely confident young man about to come into his inheritance — not an inheritance of money, he saw now, but of poetry. There could be no higher privilege and its price was sadness.” Although not without company in his solitude, Roman came to embody this truth more than most, stumbling toward that lofty ideal of the honest poet.